|

VI° CIRCUITO DEL MONTENERO 15 Agosto 1926 |

| Introduzione | Articoli | Foto | Classifica e piloti |

Percorso | Pubblicità Pubblicazioni |

Coppa del Mare | Montenero Home |

|

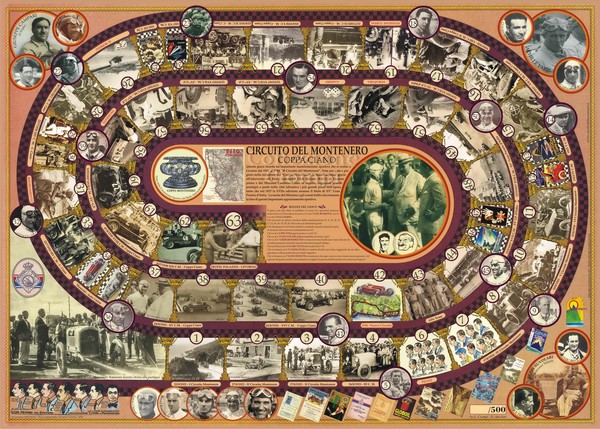

1926- 15 agosto Percorso: lunghezza 22,500 km “VI Coppa del Montenero” (10 giri - km 225) Classifica Generale 1) MATERASSI Emilio, su Itala, in 2h.55’.19’’.2/5 (media 77,000 km/h); 2) PRESENTI Bruno, su Alfa Romeo, in 3h.00’.55’’; 3) BORZACCHINI Baconin, su Salmson 1100, in 3h.03’.24’’; 4) MAZZOTTI Franco, su Bugatti, in 3h.06’.05”.2/5; 5) CORTESE Franco, su Itala, in 3h.10’.46’’; 6) VALPREDA Federico, Chiribiri 1500, 3h.11’.19’’.1/5; 7) CALIRI Antonio, su Bugatti 1500, 3h.13’.52’’.3/5; 8) STEFANELLI Ugo, su Bugatti 1500, in 3h.15’.27’’; 9) FAGIOLI Luigi, su Salmson 1100, in 3h.16’.19’’.1/5; 10) ANTONELLI Domenico, su Bugatti, in 3h.18’.16’’.3/5; 11) BECCARIA Luigi, su Ceirano 1500, in 3h.19’.58’’; 12) ZAMPIERI Alfonso, su Amilcar 1100, in 3h.28’.23’’; Giro più veloce il 6° di Materassi Emilio in 17’.11” a 78,564 km/h. Classe oltre 1500 cmc (10 giri - 225km) 1) MATERASSI Emilio, su Itala, 2h.55’.19’’.2/5 (media 77,000 km/h); 2) PRESENTI Bruno, su Alfa Romeo, in 3h.00’.55’’; 3) MAZZOTTI Franco, su Bugatti, in 3h.06’.05’’.2/5; 4) CORTESE Franco, su Itala, in 3h.10’.46’’; 5) ANTONELLI Domenico, su Bugatti, 3h.18’.16’’.3/5. Classe 1500 cmc (10 giri- 225 km) 1) VALPREDA Federico, su Chiribiri, in 3h.11’.19’’.1/5 (media 70,562 km/h); 2) CALIRI Antonio, su Bugatti, in 3h.13’.52’’,3/5; 3) STEFANELLI Ugo, su Bugatti, in 3h.15’.27’’; 4) BECCARIA Luigi, su Ceirano, in 3h.19’.58’’. Classe 1100 cmc. (10 giri - 225 km) 1) BORZACCHINI Baconin, su Salmson, in 3h.03’.24’’ (media 73,609 km/h); 2) FAGIOLI Luigi, su Salmson, in 3h.16’.19’’.1/5; 3) ZAMPIERI Alfonso, su Amilcar, in 3h.28’.23’’. (da: “L’auto italiana” del 31 Agosto 1926) |

|

|

|

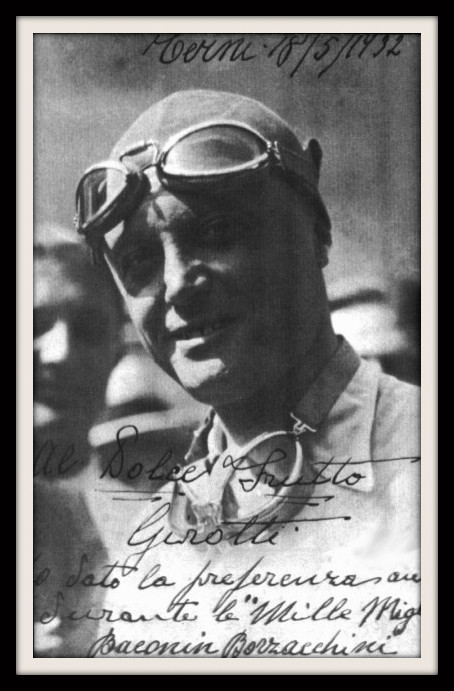

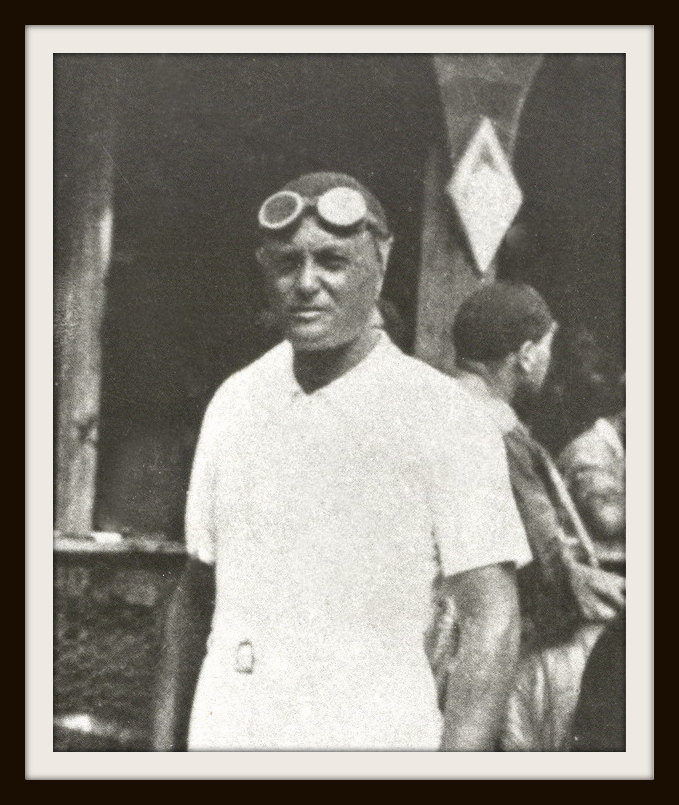

COPPA MONTENERO 1926 Circuito Montenero - Livorno (Italy), 15 August 1926. 10 laps x 22.5 km (14.0 mi) = 225 km (139.8 mi) Drivers Class up to 1100 cc (N°1) Alessandro Marino, Marino GS - 1100cc; (N°2 ) André Morel, Amilcar - 1100cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°2) Attilio Barbieri, Amilcar - 1100cc; (N°3) Mario Saetti, Sénéchal - 1100cc; (N°4) Filippo Sartorio, Gar Chapuis Dornier - 1100cc; (N°5) Elio Pistarino, Salmson - 1100cc; (N°6) Giulio Masini, Salmson - 1100cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°7) Carlo Alicandri, Gar Chapuis Dornier - 1100cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°8) Luigi Fagioli, Salmson GSS - 1100cc; (N°9) Alfonso Zampieri, Amilcar C6 – 1100cc; (N°10) Manlio Spongia, Salmson; (N°11) Baconin Borzacchini, Salmson GSS – 1100cc; Class 1101 to 1500 cc (N°12) Gusmano Pieranzi, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc; (N°14) Paolo Pavesio, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc; (N°15) Aldo Colombo, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°16) Antonio Caliri, Bugatti T37A - 1500cc; (N°18) Mario Mazzacurati, Chiribiri Monza S - 1500cc; (N°19) Pietro Cattaneo, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°20) Ugo Sisto Stefanelli, Bugatti T37 - 1500cc; (N°21) Giuseppe Pecoraio, Bugatti T22 “Brescia” - 1500cc; (N°22) Federico Valpreda, Chiribiri Monza C - 1500cc; (N°23) Luigi Beccarla, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc; (N°24) Maurizio Ciancherotti, Aurea 4000 - 1500cc; Class over 1500cc (N°25) Mario Razzauti, Alfa Romeo RL - 3000cc (DNS - practice crash); (N°26) Aymo Maggi, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc; (N°27) Emilio Materassi, Itala Spcl - 5800cc; (N°28) Domenico Antonelli, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc; (N°29) Franco Cortese, Itala 61 - 2000cc; (N°30) Giulio Aymini, Diatto 35 - 3000cc; (N°31) Renato Balestrero, OM 665 S - 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°32) Ferruccio Zaniratti, Bugatti T30 Indy - 2000cc; (N°33) Andrea Nicoli, OM 665S - 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°34) Alfredo Tremolanti, Lancia Lambda - 2100cc; (N°35) Franco Mazzotti, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc; (N°36) Emilio Bonamico, Bugatti 2000 - 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°37) Arturo Farinotti, Bugatti 2000 - 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°38) Gino Bertocci, Alfa Romeo RLTF23 - 3000cc; (N°39) Vittorio “Nino” Astarita, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc; (N°40) Bruno Presenti, Alfa Romeo RLTF24 - 3600cc; (N°41) Giorgio Ceratto, Alfa Romeo RLSS - 3000cc; (N°41) Carletto “Carlo” Rosti, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); (N°42) Maria Antonietta D'Avanzo, Mercedes GP 1914 - 4500cc (DNA - did not appear). Note: race numbers 13 and 17 were not used because they were considered to be unlucky. Materassi beats all Coppa Montenero records with his Itala Special. An assortment of 29 racecars appeared at the start of the 225 km Coppa Montenero. Materassi in his 5.8 - Liter Itala Special led the ten lap race from start to finish, winning the event for the second time. Maggi, Mazzotti and Antonelli in 2000 Bugattis, Presenti (3600 Alfa Romeo) and Cortese (2000 Itala) were unable to challenge him. Presenti finished second and the skillfully driving Borzacchini (1100 Salmson) wound up third, beating all the 2000 and 1500 cars. There were a total of 16 finishers with 13 retirements and no serious accidents on this difficult circuit. The races on the Montenero Circuit near Leghorn (Livorno) had been held since September 25, 1921 when the sportsman Paolo Fabbrini launched an event to show that Livorno could organize a car race of some importance. Corrado Lotti in an Ansaldo was the first winner. The course was also called the Circuito del Romito from 1922 onwards. The start was in Ardenza Mare at the Principe di Napoli bridge - then along Via della Torre - Via del Pastore - Via del Littorale (Ardenza) - under the railway - Via di Montenero - Via del Castellaccio - Savolano - climbing up to Castellaccio - Via di Quercianella (the new road) - and then the descent to the sea at Romito - Via Littorale - Maroccone - Via Amerigo Vespucci - Via Duca Cosimo - Via dei Bagni - Viale Vittorio Emanuele II - to the finish at Ardenza Mare. The course remained unchanged in subsequent years and was considered difficult without being dangerous, and was full of natural beauty. The narrow road twisted through 164 curves with steep gradients through the mountains and was a small replica of the Madonie in Sicily, but considerably shorter and did not allow high speeds. Ten laps had to be driven round the 22.5 km circuit, a total of 225 km. L'Automobile Club Livorno held the 1926 Coppa Montenero for its sixth running. The cars were divided into three classes, up to 1100 cc, 1101 to 1500 cc, and over 1500 cc. The overall winner would be presented with the Coppa Montenero, a challenge trophy and gift from the Mayor of Livorno. The race had a prize fund of 100,000 lire. Entries There was a break of eight days between the Coppa Acerbo and the Montenero Circuit race, giving drivers and teams little time to prepare for the new battle. Most of the better known Italian drivers appeared for the Coppa Montenero and 41 entries were received. The 1925 winner, Emilio Materassi was the favourite in his Itala Special. Count Aymo Maggi with his 2000 Bugatti was expected to challenge Materassi as were the other Bugattis of Mazzotti and Count Antonelli, and the Alfa Romeos of Presenti, Bertocci and Ceratto. Alfredo Tremolanti with his 2000 Lancia and Franco Cortese in one of the latest Itala 61s, were both from Livorno. Mario Razzauti, also a native of Livorno, crashed his Alfa Romeo during practice to the extent that it could not be repaired in time for the start. The 1500 category comprised nine cars: three Ceiranos, three Bugattis, two Chiribiris and one Aurea. The best chances for class victory were the Bugattis of Stefanelli and Caliri and the fast Chiribiri Monza of Valpreda. The eight starters in of the 1100 category consisted of three Salmsons, two Amilcars, one of each Marino, Gar and Sénéchal. The Salmsons of Borzacchini and Fagioli were most likely to win this class. A complete list of numbered entries is at the beginning of this report. The Race The officials of the “L'Automobile Club Livorno” led by their President, Cavaliere Emanuele Tron, were ready for the organization of this race at the finish line, near the entrance of the Rotonda di Ardenza. The spectators began to flow into the village of Ardenza Mare at 8:00 AM with cars, trams and every means of transport. The grandstands reverberated with spectators in elegant multi-colored summer wear. A large crowd had come to witness the the duel between Materassi and Maggi, the two most famous drivers, plus many others. The circuit was closed at 8:15 AM when the Cavaliere Piero Polese departed with the commissioners of the Automobile Club d'Italia in a fast Alfa Romeo to make sure that the barriers to the access roads were erected all around the 22.5 km circuit in order to keep the circuit clear for the race. A few minutes before 9:00 AM, the minister Count Costanzo Ciano arrived to take his place in the grandstand before the finish line. City officials and other authorities accompanied him. The megaphone announced that there were only a few minutes left and summoned the cars to their starting places. They formed a long and impressive line of 29 colorful cars occupying a good part of the avenue Vittorio Emanuele III, ready to leave. The following 13 drivers did not appear: #2 Morel (Amilcar), #5 Pistarino (Salmson), #6 Masini (Salmson), #7 Alicandri (Gar), #15 Colombo (Ceirano), #19 Cattaneo (Ceirano), #25 the Livornese Mario Razzauti (Alfa Romeo), the winner of the third Montenero race, #31 Balestrero (OM), winner of the fourth Montenero race, #33 Nicoli (OM), #36 Bonamico (Bugatti), #37 Farinotti (Bugatti), #41Rosti (Bugatti) and #42 Baroness Maria d'Avanzo (Mercedes). Because of the dusty dirt roads the cars were started individually from a standing start in order of their race numbers with intervals of 30 seconds between each car and a 1½ minute interval between each class. However, the cars were not necessarily released at 30 seconds intervals. The starting procedures were the same as seen at the Targa Florio and Mugello. This was because the start times had been determined beforehand according to their the race numbers and if particular cars did not appear at the start (e.g. #5, #6, and #7) car #8 was held to its predetermined time of departure. For instance Fagioli left 30 seconds after 9:03 AM even though the #5, #6, and #7 cars did not appear. The regulations spelled out that each driver had to start at the time that was assigned to his car. If a driver could not start, he would have to immediately move his car off the road past the starting line. The 1100cc cars were released first. The timekeepers at Count Costanzo Ciano's side counted down the seconds and at the stroke of 9:00 AM Ciano lowered the traditional flag to send off the #1 Marino of Alberto Marino to the enthusiastic applause of thousands of people who crowded the start area. After 30 seconds Barbieri started and so one after the other the cars were started individually. When Count Maggi and Emilio Materassi left the finish line, there was great cheering. When the local hero Cortese started he stopped just a few meters after the finish line for 2m.30s to change one spark plug on his Itala 61, but bravely resumed and proceeded at a fast pace. Ceratto's #41 Alfa Romeo was the last to leave at 9:21 AM. Drivers start -9:00'00" (N°1) Marino, Marino; -9:00'30" (N°2) Barbieri, Amilcar; -9:01'00" (N°3) Saetti, Sénéchal; -9:01'30" (N°4) Sartorio, Gar; -9:02'00" (N°5) DNA; -9:02'30" (N°6) DNA; -9:03'00" (N°7) DNA; -9:03'30" (N°8) Fagioli, Salmson; -9:04'00" (N°9) Zampieri, Amilcar; -9:04'30" (N°10) Spongia, Salmson; -9:05'00" (N°11) Borzacchini, Salmson - Last of class up to 1100 cc; -9:05'30" (1½ minutes interval to next higher class in effect); -9:06'00" (interval in progress); -9:06'30" (N°12) Pieranzi, Ceirano; -9:07'00" (N°14) Pavesio, Ceirano; -9:07'30" (N°15) DNA; -9:08'00" (N°16) Caliri, Bugatti; -9:08'30" (N°18) Mazzacurati, Chiribiri; -9:09'00" (N°19) DNA; -9:09'30" (N°20) Stefanelli, Bugatti; -9:10'00" (N°21) Pecoraro, Bugatti; -9:10'30" (N°22) Valpreda, Chiribiri; -9:11'00" (N°23) Beccaria, Ceirano; -9:11'30" (N°24) Ciancherotti, Aurea (Last of 1500cc class); -9:12'00" 1½ minutes interval to next higher class in effect; -9:12'30" interval in progress; -9:13'00" (N°25) DNA; -9:13'30" (N°26) Maggi, Bugatti; -9:14'00" (N°27) Materassi, Itala Spcl; -9:14'30" (N°28) Antonelli, Fiat; -9:15'00" (N°29) Cortese, Itala; -9:15'30" (N°30) Aymini, Diatto; -9:16'00" (N°31) DNA; -9:16'30" (N°32) Zaniratti, Bugatti; -9:17'00" (N°33) DNA; -9:17'30" (N°34) Tremolanti, Lancia; -9:18'00" (N°35) Mazzotti, Bugatti; -9:18'30" (N°36) DNA; -9:19'00" (N°37) DNA; -9:19'30" (N°38) Bertocci, Alfa Romeo; -9:20'00" (N°39) Astarita, Bugatti; -9:20'30" (N°40) Presenti, Alfa Romeo; -9:21'00" (N°41) Ceratto, Alfa Romeo. The crowd in the grandstand waited anxiously for the cars to pass at the end of the first lap, which would indicate the superiority of Maggi or Materassi. Saetti in the little Sénéchal passed by with a frightful skid at the curve of the stands. Fagioli and Borzacchini were very fast, but others went by almost unnoticed. Everyone was waiting for the two rivals. Finally Maggi and Materassi roared past, separated by just one second. Materassi had made up his 30 second starting time delay. Maggi finished the first lap in 17m.43.2s and Materassi in 17m.14.2s: both had beaten comfortably the old record of 18m.8s by Count Carlo Masetti. The crowd applauded excitedly at this dramatic beginning but went quiet when they saw Maggi's car come to a stop at the pits. Maggi and his mechanic changed a spark plug and he rejoined, however, having lost precious minutes. The crowd was silent. Maggi understood that this would hound him. In the meantime Mazzacurati was forced to retire his 1500 Chiribiri due to a fire on board on the first lap near Calafuria. Sartorio retired his 1100 Gar also on the first lap. The end of the second lap was awaited; but now the struggle was over. Maggi could no longer threaten Materassi. He left with only seven cylinders firing; he had replaced a dirty spark plug and continued. Instead, another change of the spark plug carried out at the end of the second lap suggested that it was a valve spring problem. After stopping on the third and fourth laps because replacing of spark plugs not working, the problem forced Maggi to retire on the fifth lap because his Bugatti was in no condition to compete. Materassi knew that he was no longer being threatened so he continued without forcing his Itala, which he had perfected by lightening it and equipping it with new brakes. All of Materassi's laps were under 17m.46s. After the third lap Aymini was forced to retire with engine problems on his Diatto. Spongia's Salmson and Bertocci's Alfa Romeo retired on lap five. Materassi continued his consistent run ahead of Presenti's Alfa Romeo and Borzacchini's 1100 Salmson which was driven very regularly. Franco Cortese, who no longer had trouble with the engine, resumed with great determination. At mid race, Materassi was leading with the field in the following order after lap five: 1. Materassi (5800 Itala Spcl) 1h.27m.25.0s; 2. Presenti (3600 Alfa Romeo) 1h.30m.07.4s; 3. Borzacchini (1100Salmson) 1h.32m.12.0s; 4. Mazzotti (2000 Bugatti) 1h.33m.20.4s; 5. Antonelli (2000 Bugatti) 1h.33m.25.4s; 6. Astarita (2000 Bugatti) 1h.35m.01.0s; 7. Zaniratti (2000 Bugatti) 1h.35m.11.0s; 8. Valpreda (1500 Chiribiri) 1h.35m.32.6s; 9. Pecoraro (1500 Bugatti) 1h.36m.37.0s After the 5th lap Tremolanti's Lancia slowed down with two punctures and he also had to secure a loosened fuel tank. On the 6th lap Materassi made a fast time in 17m.11s at the average of 77.564 km/h, which proved to be the fastest lap of the race lowering the previous record of Carlo Masetti in 18m.8s by almost a minute, and also raised his total average from 68.641 km/h to 77 km/h. Astarita's Bugatti ended the race on the sixth lap. Borzacchini improved his pace lap by lap until reaching a lap time of 18m.03.6s on lap 7, which was also below Masetti's old lap record. He did all this with style and ease without driving dangerously. Ceratto retired his Alfa Romeo on the seventh lap as did Tremolanti with the Lancia. On the 8th lap Borzacchini was in second place. Presenti's Alfa Romeo had gained 1m.30s on Borzacchini who encountered a puncture and was forced to stop for a repair, losing his second place. Giuseppe Pecoraro, who retired on the last lap, had driven fantastically and also made the fastest lap in the 1500 class. Zaniratti, who raced the Indianapolis Bugatti, had to stop on the last lap when a connecting rod broke. From the beginning of the last lap Materassi was acclaimed by the enthusiastic crowd and was celebrated at the finish after 2h.55m.19.4s. Materassi was carried in triumph to the grandstand where the officials were waiting to greet him. Costanzo Ciano shook his hand and congratulated him on the wonderful victory. Bruno Presenti finished second, a wise man who knew his business; he drove a good race. Borzacchini with his 1100 Salmson ranked third overall and beat all two-liter cars, including Bugatti, all one and a half liter and men who were not the slowest ones. The young new star, who rose this season to tarnish the glory of the elderly, was the man who shone most after the overall winner in this race. Franco Mazzotti finished fourth; he could and should do more. The long absence from racing had damaged him more morally than physically. He was not very combative and immediately gave in to the first set of tires that made him lose about 4 minutes along the course. Franco Cortese from Livorno finished in fifth place and was welcomed with particular affection, receiving a beautiful bouquet of flowers from Count Ciano. Cortese lost 2m.30s at the start for changing one spark plug but fought hard to make up the lost time. His fifth place is very honorable, considering that he raced with a normal Itala 61 chassis. In sixth place finished Federico Valpreda, winning the 1500 class and beating his direct opponent Ugo Sisto Stefanelli, who seemed to be the favorite. Stefanelli partly owed his defeat to poor preparation. He arrived the evening before the race in Livorno and started without ever practicing. This was a luxury that even the great champions do not allow themselves. In ninth place finished the excellent Fagioli. Count Domenico Antonelli ended the race in tenth place, but, unlucky forever, he had several incidents that delayed him and that lost him several places in the results. Results 1°(N°27) Emilio Materassi, Itala Spcl - 5800cc (Laps 10) 2h.55m.19.4s; 2°(N°40) Bruno Presenti, Alfa Romeo RLTF24 - 3600cc (Laps 10) 3h.00m.55.0s (+ 5m.35.6s); 3°(N°11) Baconin Borzacchini, Salmson GSS - 1100cc (Laps 10) 3h.03m.24.0s (+ 8m.04.6s); 4°(N°35) Franco Mazzotti, Bugatti 2000 - 2000cc (Laps 10) 3h.06m.05.4s (+ 10m.46.0s); 5°( N°29) Franco Cortese, Itala 61 - 2000cc (Laps 10) 3h.10m.46.0s (+ 15m.26.6s); 6°(N°22) Federico Valpreda, Chiribiri Monza C - 1500cc (Laps 10) 3h.11m.19.2s (+ 15m59.8s); 7°(N°16) Antonio Caliri, Bugatti T37A - 1500cc (Laps 10) 3h.13m.52.6s (+ 18m.33.2s); 8°(N°20) Ugo Sisto Stefanelli, Bugatti T37 - 1500cc (Laps 10) 3h.15m.27.0s (+ 20m.07.6s); 9°(N°8) Luigi Fagioli, Salmson GSS - 1100cc 3h.16m.19.2s (+ 20m.59.8s); 10°(N°28) Domenico Antonelli, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc (Laps 10) 3h.18m.16.6s (+ 22m.57.2s); 11°(N°23) Luigi Beccaria, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc (Laps 10) 3h.19m.58.0s (+ 24m.38.6s); 12°(N°9) Alfonso Zampieri, Amilcar C6 - 1100cc (Laps 10) 3h.28m.23.0s (+ 33m.03.6s). 13°(N°24) Maurizio Ciancherotti,, Aurea 4000 - 1500cc(Laps 10) 3h.30m.43.4s (+ 35m.24.0s); 14°(N°1) Alberto Marino, Marino GS - 1100cc (Laps 10) 3h.32m.41.6s (+ 37m.22.2s); 15°(N°3) Mario Saetti, Sénéchal - 1100cc (Laps 10) 3h.34m.05.4s (+ 38m.46.0s); 16°(N°14) Paolo Pavesio, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc (Laps 10) 3h.39m.49.0s (+ 44m.29.4s); DNF(N°12) Gusmano Pieranzi, Ceirano S150 - 1500cc (Laps 9); DNF(N°21) Giuseppe Pecoraro, Bugatti T22 - 1500cc (Laps 9); DNF(N°32) Ferruccio Zaniratti, Bugatti T30 Indy - 2000cc (Laps 9); DNF(N°41) Giorgio Ceratto, Alfa Romeo RL SS - 3000cc (Laps 6); DNF(N°34) Alfredo Tremolanti, Lancia - 2100cc (Laps 6); DNF(N°39) Vittorio “Nino Astarita, Bugatti 2300 - 2300cc (Laps 5); DNF(N°10) Manlio Spongia, Salmson - 1100cc (Laps 4); DNF(N°26) Aymo Maggi, Bugatti T35 - 2000cc (Laps 4) (spark plugs); DNF(N°38) Gino Bertocci, Alfa Romeo RLTF23 - 3000cc (Laps 4); DNF(N°30) Giulio Aymini, Diatto 35 - 3000cc (Laps 2) (engine); DNF(N°2) Attilio Barbieri, Amilcar - 1100cc (Lap 1); DNF(N°4) Filippo Sartorio, Gar Chapuis Dornier - 1100cc (Lap 1); DNF(N°18) Mario Mazzacurati, Chiribiri Monza S - 1500cc (Lap 0) (fire). Fastest lap, over 1500cc: Emilio Materassi (Itala Spcl.) on lap 6 in 17m.11s = 78.6 km/h (48.8 mph). Fastest lap, 1500cc: Giuseppe Pecoraro (Bugatti) in 18m.27.6s = 73.1 km/h (45.4 mph). Fastest lap, 1100cc: Baconin Borzacchini (Salmson) on lap 7 in 18m.03.6s = 74.6 km/h (46.4 mph). Winner's average speed over 1500cc, Materassi: 77.0 km/h (47.8 mph). Winner's average speed 1500cc, Valpreda: 70.6 km/h (43.8 mph). Winner's average speed 1100cc, Borzacchini: 73.6 km/h (45.7 mph). Weather: sunny, dry. (by Hans Etzrodt in: The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing) MARIO UMBERTO BACONIN BORZACCHINI Ma quanto avrà pesato sul giovane Borzacchini quel nome così impegnativo, Baconin, mutuato dal mitico Bakunin russo a cui il padre, comunista sfegatato ed eroico, si era ispirato per battezzare, nel 1898, il suo unico figliolo? Ce lo immaginiamo, nei cortili assolati di scuola, tra compagni burloni e pesanti di mano, rispondere all’appello del maestro mentre pronunciava il nome sacro al marxismo. Ma ancora più è immaginabile il suo disagio negli anni tronfi e sospettosi del fascismo, a dover magari rispondere all’appello del caporale, negli anni di leva, o in quelli promettenti dell’esordio da pilota, quando una settimana su due il suo nome era riportato sulle cronache sportive ternane! Molto meno bastava, in quei tempi, per essere giudicato di insufficiente fede fascista, ed essere anche, in quanto personaggio pubblico, richiamato all’ordine. Borzacchini si portò con sé, pazientemente, questo nome ingombrante per ben trentadue anni. Finché, come ci racconta Remo Tomassini, suo biografo ed amico d’infanzia (“Borzacchini, l’uomo, il pilota, il suo tempo”, ACI Terni, 1983), quando era già pilota affermato della squadra Alfa Romeo, si trovò a far fare un giro d’onore sull’Autodromo di Monza alle Loro Altezze Reali il Principe di Piemonte Umberto di Savoia e la sua Consorte Principessa Maria José del Belgio. Potenza del potere! L’incontro spazzò via in un solo colpo gli anni di intensa ed appassionata educazione marxista del padre. Al termine della giornata, Borzacchini pretese che il nome sovversivo venisse cancellato per sempre e chiese di essere chiamato, in loro onore, Mario Umberto. La figura di questo pilota non è tra le più conosciute del periodo. Fu pilota di vetturette, e di vetture da Grand Prix; corse con Ansaldo e Salmson, e quindi fu ingaggiato da Maserati ed Alfa Romeo. Gareggiò spesso contro, ma ancor più spesso in coppia con Nuvolari, con cui creò un tandem di singolare sintonia. E morì ancora giovane, in una tragica giornata del settembre 1933, a Monza, insieme a due altri grandi campioni, Campari e Czaikowski. Manca nella sua biografia il gesto esemplare, la giornata del trionfo assoluto, la scintilla che trasforma un asso conosciuto ed apprezzato dagli appassionati in un idolo dal nome scandito dalle folle. In realtà ci fu questa giornata, e davvero Borzacchini divenne in quell’occasione un nome famoso in tutto il mondo. Ma evidentemente il suo nome non conteneva in sé quella sonorità misteriosa che contribuisce a creare la leggenda (Nuvolari, quell’accenno al cielo, al suo aspetto mutevole e burrascoso e veloce; Varzi, che sembra uno sparo…): e il ricordo di queste pagine, alla distanza esatta di settant’anni, vuole essere un gesto di ricordo e di celebrazione di un bel campione. Quando Borzacchini fa parlare di sé nel mondo, è ancora Baconin, e non c’era presagio della sua fulminante conversione alla monarchia. Fu nel settembre 1929, quando conquista il “Record Mondiale di Velocità sui dieci chilometri lanciati”, a Cremona, con una Maserati 16 cilindri, migliorando di ben 20 chilometri il precedente record stabilito dall’inglese Eldridge su Fiat. Vettura, quest’ultima, dotata di un mostruoso motore d’aviazione, di 21,7 litri di cilindrata (contro i 4 della Maserati), in grado di sviluppare 320 CV a 1800 giri/1’: la spaventosa “Fiat Mefistofele”, ora conservata al Centro Storico Fiat di Torino. L’impresa fu davvero memorabile, più di quanto possa forse essere comprensibile adesso, e per diversi motivi. Innanzitutto per l’eccezionale risultato assoluto conseguito dal pilota ternano: 247,933 km/h sul rettilineo di andata (incorporato nel circuito di Cremona vero e proprio), 244,233 km/h nel tratto di ritorno, per una media complessiva di 246,069 km/h. Migliorare di venti chilometri il record precedente è un successo inaudito, e la sproporzione delle cilindrate, a sfavore di Borzacchini, rende il tutto ancora più clamoroso. Inoltre la vettura su cui si cimenta Borzacchini non è una macchina preparata appositamente per il record (come invece la Fiat Mefistofele), tant’è vero che la stessa vettura è iscritta alla corsa delle 200 miglia che si sarebbe disputata il giorno dopo. E infine si era trattato di una velocità raggiunta e mantenuta per una distanza data, anziché soltanto sfiorata come succede con i records sul chilometro lanciato. La sedici cilindri Maserati risulta dall’accoppiamento di due motori ad otto cilindri in linea con doppio albero a cammes in testa; totalizza esattamente 3960 cc, ed eroga una potenza di 250CV ai quali si aggiungono un’altra quarantina di cavalli forniti dai due compressori. Due sono anche i carburatori, e l’alimentazione costituita da una miscela di benzina, benzolo ed etere, preparata dallo stesso Alfieri Maserati. Per la cronaca, gli avversari di Borzacchini in quell’occasione sono Gastone Brilli-Peri e Achille Varzi sull’intramontabile Alfa Romeo P2, e Tazio Nuvolari sulla Bugatti 3000. Vincente è la scelta, da parte di Borzacchini, di puntare su una giovane casa italiana come la Maserati, che aveva stentato fino a quel momento a dimostrare il proprio valore. Eppure Baconin ci crede fermamente. Qualche mese prima, in aprile, ha partecipato alla Mille Miglia con una due litri sport, in coppia con Ernesto Maserati. La vettura non risulta inserita nella rosa dei possibile vincitori neppure come sorpresa dell’ultimo minuto, e difatti la classifica rispetta le previsioni, la Maserati è costretta a ritirarsi a Terni (proprio a Terni, città natale di Borzacchini, ironia della sorte!), dopo quasi 700 km di corsa, per un guasto irrimediabile del cambio. Ma quei 700 chilometri sono stati percorsi da veri dominatori; primi a Bologna alla media di 127,300 con 4 minuti di vantaggio su Campari (e battendo di tre minuti circa il precedente record di Nuvolari); primi a Firenze a 101 km/h, e sei minuti di vantaggio su Campari; primi a Roma alla media di 92,087, ancora in testa di quattro minuti su Campari nonostante uno stop; e ancora in testa a Terni, a maggior rabbia e delusione degli amici e compagni di Borzacchini. Il giovane, timido Borzacchini, per essersi fatto da solo non poteva lamentarsi dei risultati, con i suoi dieci primi posti assoluti (tra cui la straordinaria Mille Miglia del 1932, la Susa Moncenisio del 1933, la Pontedecimo Giovi del 1930 e 1932), ventuno secondi posti assoluti, e trentuno vittorie di classe, stava davvero avviandosi ad una buona carriera. Per le mani gli era passata (a parte l’Ansaldo 4CS, carrozzata quattro baquets, 2000 cc, 48 CV dell’esordio nel 1923), la francese Salmson Grand Prix del 1925 con cilindrata 1100, una vettura dotata di ottimo motore ma con un sistema di frizione ancora primitivo (a cono di cuoio rovesciato) e soprattutto priva di differenziale. Questo particolare faceva sì che, in qualsiasi curva, la ruota interna, girando alla stessa velocità di quella esterna, spingesse “naturalmente” la vettura fuori strada, per un elementare principio di dinamica che la maestria del pilota poco valeva a contrastare. A questo aggiungiamo un deciso “molleggio”, determinato da balestre semiellittiche all’avantreno e mezzi balestrini posteriori, incapaci di assorbire le asperità del fondo stradale. I freni, inoltre sembra non fossero molto efficaci, ma questo era l’unico dettaglio tecnico a non impensierire Borzacchini. Nel 1926, grazie a consistenti premi gara, il pilota riesce ad acquistarsi una Salmson San Sebastiano, cosiddetta dopo la vittoria al Gran Premio vetturette del 1925, disputato nella città basca. Questa versione ha una cilindrata di 1193 cc, doppio albero a camme in testa, pistoni in alluminio, doppia accensione. Con 350 kg di peso può anche raggiungere i 160 km/h: un piccolo bolide. Poi arriva l’ingaggio con Maserati: la 1500, la 1700, la 26 B e la magnifica 16 cilindri di Cremona. Nel 1930, dopo un’avventura infelice ad Indianapolis, ma anche un primo posto assoluto al Gran Premio di Tripoli, ecco la proposta di ingaggio da parte di Alfa Romeo, che Borzacchini, opportunamente, coglie al volo. Esordisce con un’Alfa 1750 con cui vince subito la Pontedecimo – Giovi alla media di 82,033 km/h, nuovo record. I suoi compagni di strada sono Varzi, Nuvolari, Campari. L’anno dopo, alla Mille Miglia, sono tutti schierati contro il solo Caracciola su Mercedes…e perdono tutti. Borzacchini deve cambiare 11 gomme; Nuvolari 14. Ma una cronaca del R.A.C.I. precisa impietosa: “Borzacchini prosegue indomabile anche dopo la rottura dei freni finché, rimasto anche senza gomme di ricambio, continua la sua marcia sui cerchioni finché la macchina può rotolare sulla strada…”A dimostrazione che per Borzacchini i freni continuano ad essere un optional, gradito ma non indispensabile. Sempre nel 1931 al ternano viene affidata l’Alfa 2300, con cui vince al Tourist Trophy e soprattutto, l’anno dopo, la Mille Miglia in coppia con Amedeo Bignami, alla media di 109,884 km/h, migliorando il record di Caracciola dell’anno prima, su Mercedes 7000. E così si è arrivati alla macchia d’olio del Gran Premio di Monza del 1933. Il 10 settembre di quell’anno si organizza a Monza nella stessa giornata il Gran Premio d’Italia e il Gran Premio di Monza, con due percorsi e formula diversi, a cui si iscrivono tutti i grandi campioni (eccetto Varzi), e le migliori vetture, le Alfa Romeo P3, una Bugatti 8 cilindri, due Maserati 3000, di cui una monoposto e una biposto, una Duesenberg 8 cilindri. La prima gara, il Gran Premio d’Italia, si corre alla mattina ed è vinto da Fagioli davanti a Nuvolari. Nel pomeriggio, il Gran Premio di Monza, in tre batterie su 14 giri della sola pista, e in una finale su 22 giri, a cui sarebbero stati ammessi i primi quattro di ogni batteria. Il caso vuole che durante la prima batteria Trossi (su Duesenberg) subisca un’avaria ad un pistone, con conseguente rottura del carter dell’olio e spargimento dell’olio all’imbocco della curva Sud. Arrivata la prima batteria, una vettura chiusa dal cui finestrino sporgeva una lunga scopa va a spazzare il terreno di gara. Alle 15 parte la seconda batteria, formata da Campari, Balestrero, Barbieri, Castelbarco e Hellé Nice su Alfa Romeo, e Borzacchini su Maserati. Campari e Borzacchini imboccano a tutto gas la curva nord…ed è il silenzio. Dopo qualche istante ripassano davanti alle tribune Balestrero e la Hellé Nice: per un giro, due, tutti e quattordici. Degli altri quattro piloti nessuna traccia, e soprattutto nessuna notizia (sembra che l’altoparlante per spezzare la tensione desse notizia del ritrovamento del solito bimbo smarrito). In realtà era successo l’inferno. All’inizio della curva sud, Campari, che era sulla destra, era slittato verso sinistra sull’olio perso dalla Duesenberg e dopo aver percorso un buon tratto proprio sull’orlo della curva, aveva demolito un blocco di cemento ed era precipitato dalla scarpata. Borzacchini, che per superare Campari si teneva a sinistra, frenò di colpo, perse il controllo della vettura e volò nel prato. La stessa cosa successe a Castelbarco e a Barbieri, ma finirono fuori strada in maniera meno spettacolare. Sia Borzacchini sia Campari, si scoprì in seguito, per alleggerire le macchine e renderle più veloci avevano smontato i tamburi dei freni anteriori… Il povero Campari era morto sul colpo, schiacciato sotto la macchina. La Maserati di Borzacchini invece aveva sbalzato fuori il pilota, che fu ritrovato ad alcune decine di metri, sul prato, ancora vivo, anche se per poco. E se si pensa che nel passato si fosse più gentili e rispettosi verso i morti, la cronaca impone di ricordare che le batterie proseguirono e si arrivò alla finale, che partì regolarmente. Ma durante la corsa, la Bugatti di Czaikowski, a pochi metri dal punto fatale a Campari, sbanda , esce di strada, si capovolge, si incendia. Il pilota muore carbonizzato all’interno della vettura. L’altoparlante continua a tacere anche questo incidente, il vincitore Lehoux è proclamato. Donatella Biffignandi |

| |

| |