|

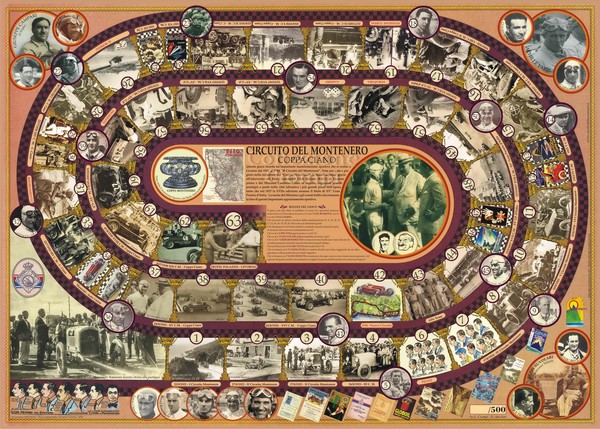

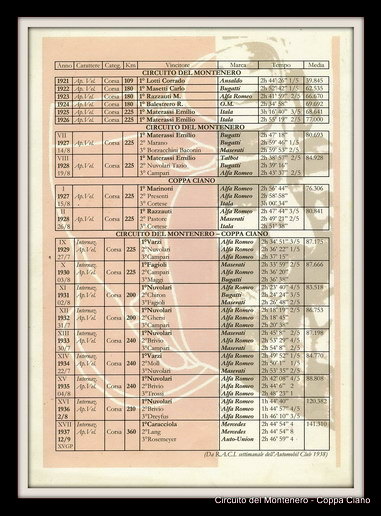

XII° CIRCUITO DEL MONTENERO

|

| Introduzione | Articoli | Foto | Classifica e piloti |

Percorso | Pubblicità Pubblicazioni |

Coppa del Mare | Montenero Home |

|

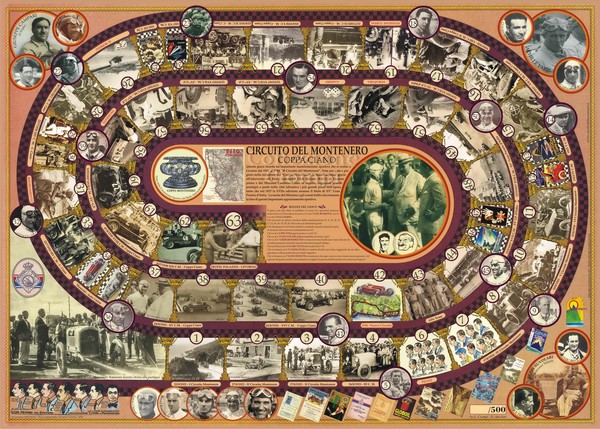

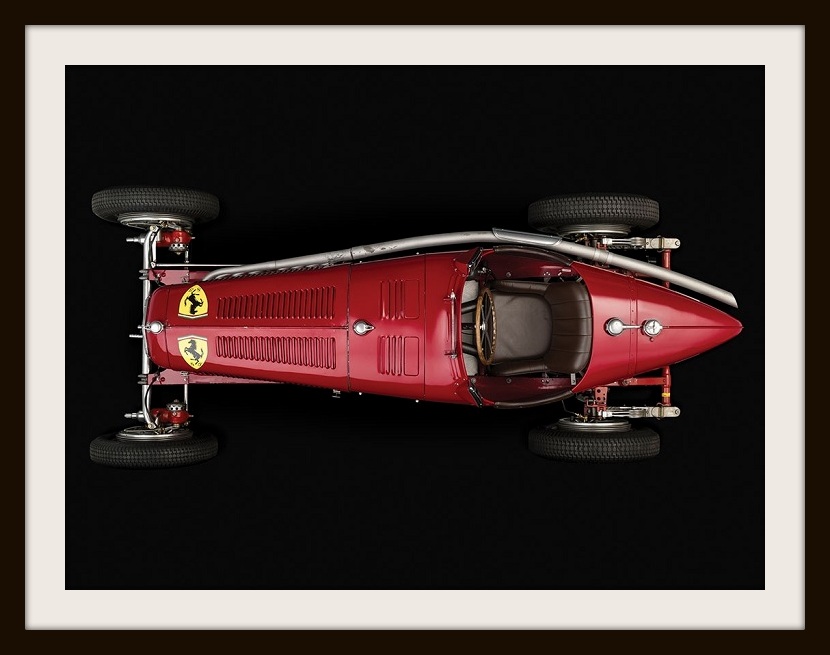

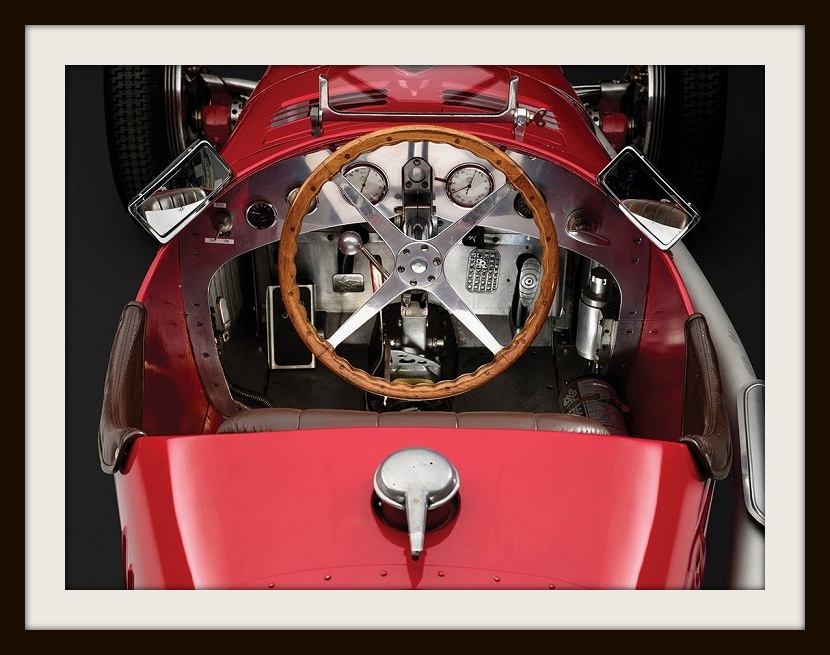

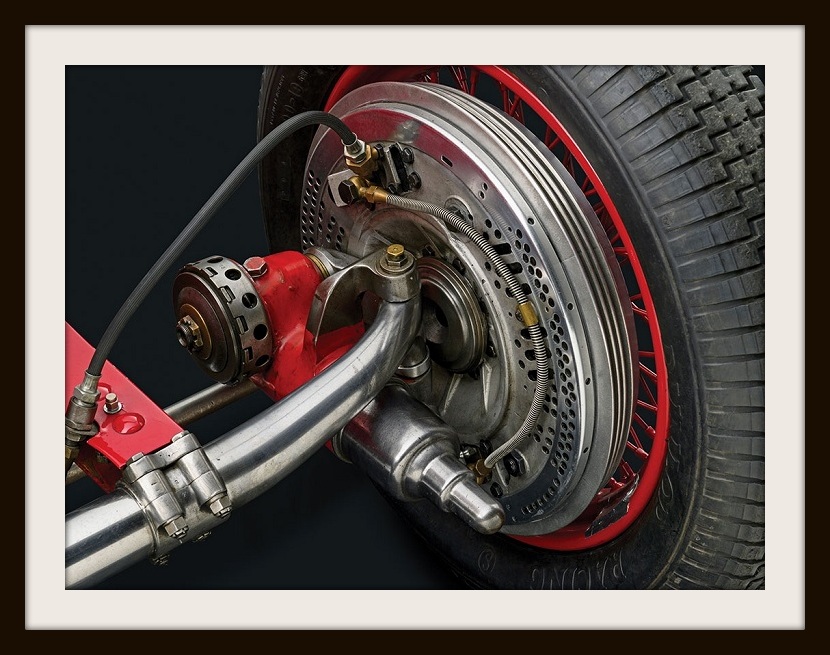

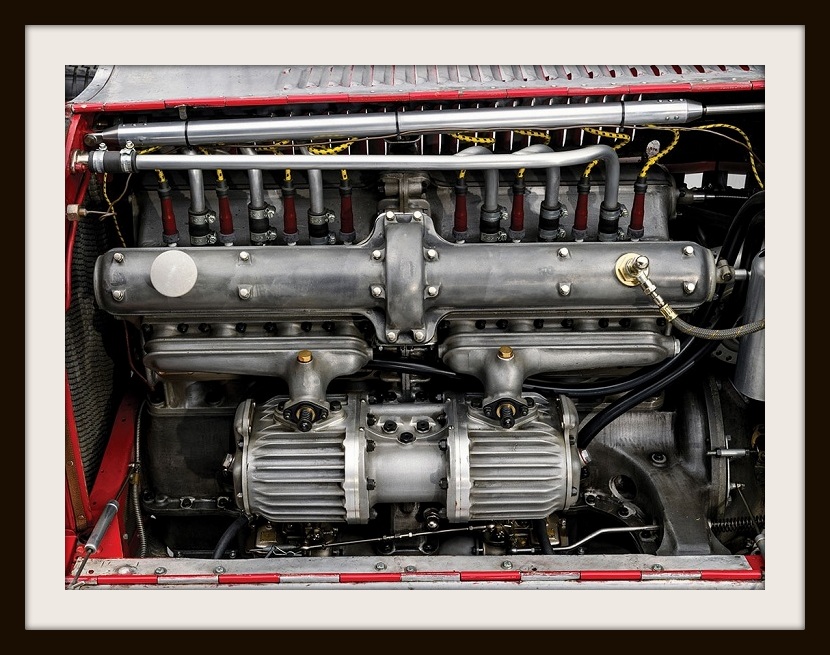

1932- 31 luglio Percorso: lunghezza 20,000 km “XII Circuito del Montenero - Coppa Ciano” Formula Libera oltre 1100 cmc (10 giri- 200 km) 1) NUVOLARI Tazio, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h 18’19”2/5 (media 86,753 km/h); 2) BORZACCHINI Mario Umberto, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.18’.45”; 3) CAMPARI Giuseppe, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.20’.38”; 4) VARZI Achille, su Bugatti, in 2h.20’.56”; 5) TARUFFI Piero, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.24’.30”.2/5; 6) GHERSI Pietro, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.24’.55”.3/5; 7) BRIVIO Antonio, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.24’.56”.1/5; 8) D’IPPOLITO Guido, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.27’.44”.1/5; 9) BALESTRERO Renato, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.37’.57”; 10) CASTELBARCO Luigi, su Maserati, in 2h.39’.45”. Giro più veloce il 3° di Nuvolari Tazio in 13’.42”.1/5 a 87,570 km/h. Vetturette 1100 cmc (8 giri - 160 km) 1) CERAMI Domenico, su Maserati, in 2h.04’.29”.1/5 (media 77,116 km/h); 2) MATRULLO Francesco, su Maserati, in 2h.10’.01”.3/5; 3) PRATESI Albino, su Salmson, in 2h.13’.33”; 4) DEL RE Luigi, su Fiat-Lombard, in 2h. 24’.00”; Giro più veloce il 3° di Cerami Domenico in 14’.53”.4/5 a 80,554 km/h. (Da: Maurizio Mazzoni: “Lampi sul Tirreno”, Firenze 2006) CIRCUITO MONTENERO 1932 (VI COPPA CIANO) Montenero – Livorno (Italy), 31 July 1932. Over 1100cc: 10 laps x 20.0 km (12.4 mi) = 200.0 km (124.3 mi) Below 1100cc: 8 laps x 20.0 km (12.4 mi) = 160.0 km (99.4 mi) Drivers Class over 1100 cc: 2 Secondo Corsi, Maserati 26 -1500cc; 4 Achille Varzi, Bugatti T51 -2300cc; 6 Silvio Rondina, OM 665 -2200cc; 8 Clemente Biondetti, Maserati Special -2500cc; 10 Luigi Castelbarco, Maserati 26M -2500cc; 12 Eugenio Fontana, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 14 Vittoria Orsini, Maserati 26 -1500cc; 16 Renato Balestrero, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 18 Carlo Gazzabini, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 20 Giovanni Salvati, Alfa Romeo 6 C1750 -1800cc (DNA did not appear); 22 Renato Cappagli, Bugatti T35B -2300cc (DNA did not appear); 24 Umberto Berti, Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 -1800cc (DNA did not appear); 26 Giuseppe Campari, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 28 Giovanni Minozzi, Bugatti T35C -2000cc (DNA did not appear); 30 Tazio Nuvolari, Alfa Romeo Tipo B/P3 -2600cc; 32 Carlo Cazzaniga, Bugatti T35B - 2300cc (DNA did not appear); 34 Piero Taruffi, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 36 Mario Umberto Borzacchini, Alfa Romeo Tipo B/P3 -2600cc; 38 Mario Tadini, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (DNA did not appear); 40 Julio Villars, Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 -1800cc (DNA did not appear); 42 Pietro Ghersi Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 44 Guido D'Ippolito, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 46 Antonio Brivio, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc; 48 Renato Danese, Bugatti T35C - 2000cc (DNA did not appear); 50 Luigi Premoli, B.M.P. 3000cc; 52 Ferdinando Barbieri, Maserati 26 -1500cc (DNA did not appear); Class up to 1100 cc 60 Domenico Cerami, Maserati 4CM -1100cc; 62 Luigi Del Re, Fiat-Lombard AL3 -1100cc; 64 Francesco Matrullo, Maserati 4CM -1100cc; 66 Savelli, Talbot 700 (DNA did not appear); 68 Levi, Salmson -1100cc (DNA did not appear); 70 Carlo Gazzabini, Alfa Romeo 6C1500 -1500cc (DNA did not appear); 72 Giulio Aymini, Monaco Jap (DNA did not appear); 74 Albino Pratesi, Salmson 1100cc; 76 Luigi Platè, Talbot 700 (DNA did not appear); 78 Cambi Salmson 1100cc; 80 Filippo Ardizzone Fiat 1100; 82 Amedeo Ruggeri Maserati 26C -1100cc; 84 Renato Cappagli Bugatti (DNA did not appear); Nuvolari wins the Coppa Ciano The end of the international motor sport week at Livorno consisted of the 200 km race for the Coppa Ciano. The Swiss driver Villars was the only foreign entry in this otherwise national race in which the presence of the Alfa Romeo works team contributed extra importance. The only serious competition to Nuvolari, Borzacchini and Campari in works Alfa Romeos came from their countryman Varzi in his red Bugatti. The remaining entries played only a statistical role and consisted of eight Alfa Romeos, four Maseratis, two specials, one OM and one Bugatti. Nuvolari won in new record time, followed by his two teammates, then Varzi who had to be content with fourth place ahead of four Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Monzas. Two independent entries were the last finishers. From the 17 starters only 10 cars reached the finish in time. The remaining cars retired, except for Biondetti who crashed his MB-Speciale and was lucky to survive. Six cycle cars raced concurrently with the grand prix cars in a separate class up to 1100 cc. Principe Cerami won this 160 km race ahead of Matrullo, both in Maseratis, followed by Pratesi and del Re, who were the only other finishers. The Montenero circuit races near Leghorn (Livorno) had been held since 1921. From 1922 onwards a 22.5 km circuit was used, which in 1931 was shortened to 20 km and routed from Ardenza Mare - Montenero - Savolano - Castellaggio - and back to Ardenza Mare. The 1932 event was the 12th time that the race was held on the Circuito del Montenero and the organizer named it misleadingly the 12th Coppa Ciano but in reality,1932 was the 6th Coppa Ciano. The Coppa or trophy was donated by Italian Navy hero Costanzo Ciano for a 1927 Montenero sports car race, which was named after the trophy. The Coppa Ciano name was applied for the second time to the 1928 Montenero sports car race. As of 1929, when the sports car race was dropped from the program, the Coppa Ciano name was assigned to the racecar event for the first time. The races were held annually and 1932 was the sixth running of the Coppa Ciano and the twelfth race on the Montenero circuit. The Coppa Ciano race took place on the same day of the first Nice Grand Prix in France. The Italian event on the Montenero Circuit was considered the more important of the two because of its long tradition plus works entries from Alfa Romeo and results counting for the Italian Championship. The 20 km circuit had to be lapped ten times by the cars over 1100 cc and the smaller cars up to 1100 cc had to cover only eight laps. Entries The class over 1100 cc received 26 entries of which the main contenders came from S.A. Alfa Romeo with two 2.6-liter monoposti for Tazio Nuvolari and Mario Umberto Borzacchini plus a 2.3-liter Monza for Giuseppe Campari. The strongest rival to this formidable team was last year's winner Achille Varzi in his red 2.3-liter Bugatti. Four additional independent Bugatti entries were received from Cappagli, Giovanni Minozzi, Carlo Cazzaniga and Renato Danese. The Scuderia Ferrari sent four 2.3-liter Alfa Romeo Monzas for Piero Taruffi, Pietro Ghersi, Guido D'Ippolito and Conte Antonio Brivio. Another seven independent Alfa Romeos were entered by Eugenio Fontana, Renato Balestrero, Carlo Gazzabini and Mario Tadini in 2.3-liter Monzas, also Giovanni Salvati, Umberto Berti and Julio Villars in 6C 1750s. Maserati was represented by four independent entries by Secondo Corsi, Conte Luigi Castelbarco, Signora Vittoria Orsini and Ferdinando Barbieri. Clemente Biondetti brought his MB Speciale and Conte Luigi Premoli his PBM, both hybrids of Bugatti and Maserati origin. The up to 1100 cc cycle car class comprised 13 entries which are listed at the beginning of this report. All cars were from independents except Amedeo Ruggeri's Maserati, which was the only factory car. Luigi Platè entered two of the odd Talbot "700-s" that were first raced in 1931. The 1500cc 8-cylinder engines were altered to comply with 1100 cc engine size by having two of their pistons removed. Practice Some of the Thursday practice times were published: Nuvolari in 15m.8.4s, Borzacchini in 13m.56.2s and Campari in 14m.24.6s. On Friday Varzi was registered at 13m.57.8s, Taruffi 14m.58.4s, Ghersi 14m.57.2s, D'Ippolito 16m.15.6s and Fontana in 16m.43.2s. In the small car class Prince Cerami's best time was 16m.2.4s while Matrullo was stopped at 17m.38.2s. The practice times had no influence on the starting positions since the starting grid was based upon the race numbers, which were drawn by lots. Race A crowd of 60 000 spectators witnessed the race, which was attended by the donor of the Cup, Signor Ciano, Minister of Communications, Vincenzo Florio and other luminaries. Some drivers withdrew, which were Salvati (Alfa Romeo), Cappagli (Bugatti), Minozzi (Bugatti), Cazzaniga (Bugatti), Tadini (Alfa Romeo), Villars (Alfa Romeo) and Danese (Bugatti). Additionally, Gazzabini and Barbieri also did not appear at the start, which reduced the field to 17 cars. The twisting and hilly Montenero Circuit was considered too dangerous for a massed start. Consequently the cars were sent off three at a time with a minute interval to the next row, so that the entire starting procedure lasted just over five minutes, starting at 3:30 PM for the first three. The official Alfa Romeo team cars were in the fourth and fifth groups leaving the start. The small car class followed after a one minute delay after the last of the large cars. Only six cars of the class up to 1100 cc started because Savelli (Talbot), Levi (Salmson), Aymini (Monaco), Platè (Talbot), Ardizzone (Fiat), Gazzabini (Alfa Romeo) and Cappagli (Bugatti) had withdrawn. Grid (N°6) Rondina.........(N°4) Varzi................(N°2) Corsi (N°12) Fontana.......(N°10) Castelbarco..(N°8) Biondetti (N°18) Gazzabini... (N°16) Balestrero......(N°14) Orsini (??)...........................(??).......................(N°26) Campari (N°36) Borzacchini..(N°34) Taruffi ….(N°30) Nuvolari ….................…..............(??)............................(??)............. (N°64) Matrullo........(N°62) Del Re....(N°60) Cerami (N°82) Barbieri........(N°78) Cambi...........(N°74) Pratesi The first driver to complete lap one was Varzi in 14m.08s, then came Biondetti over two minutes later, but he stopped at his pit to change spark plugs in 1m.30s, then joined the race again. Corsi arrived next in third place almost three minutes behind Varzi, then Campari, Ghersi, Rondina and Brivio. When Nuvolari passed the finish line after 13m.52s, there was great applause. He was followed by Balestrero, Borzacchini, Fontana, Castelbarco, Taruffi, Orsini and D'Ippolito. Gazzabini and Premoli's arrival was not mentioned in the reports. Since the cars had started at different times, their positions on the track were different from their actual race order, which was as follows: 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) (13m.52s); 2. Varzi (Bugatti) (14m.08s); 3. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) (14m.05s); 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) (14m.22s); 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) (14m.26s); 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) (14m.42s); 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) (14m.50s); 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) 14m.57s; 9. Castelbarco (Maserati) (no time); 10. Biondetti (M-B Speciale) (15m.08s); 11. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) (16m.00s); 12. Corsi (Maserati) (16m.51s); 13. Fontana (Alfa Romeo) (17m.07s); 14. Rondina (OM) (17m.45s); 15. Signora Orsini (Maserati) (17m.56s). On the first lap Premoli had a bad crash at the descent towards Calafuria where his 2.8-liter BMP hit a stone road marker, lost a rear wheel, spun, overturned and fell into a small ravine. He injured his shoulder and suffered other severe injuries. The unfortunate bleeding Premoli was put in an ambulance and taken to the Rosignano Solvay hospital, where his condition was not considered life-threatening. Giovanni Lurani wrote, "Gigi Premoli with his special car had the most frightening accident, knocking his head so seriously that he had to remain out of action for over a year." In the 1100 cc class Cerami (Maserati) was first in 15m.57s, followed by Matrullo (Maserati) 16m.15s, Pratesi (Salmson) 16m.52s, Ruggeri (Maserati) 17m.04s and Del Re (Fiat) 17m.50s. Varzi completed the second lap in 14m.01s, Nuvolari in 13m.55s. However Borzacchini established a new record lap in 13m.46.2s at an average speed of 87.146 km/h, which enabled him to overtake Varzi. Signora Orsini retired due to sickness. The positions at the end of lap two were: 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) (27m.47s); 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) (27m.52s); 3. Varzi (Bugatti) (28m.09s); 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) (28m.28s); 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) (28m.45s); 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) (29m.18s); 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) (29m.25s); 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) (29m.51s); 9. Castelbarco (Maserati) (31m.24s); 10. Biondetti (M-B Speciale) (31m.58s). In the small car class the battle between Matrullo and Cerami continued. Cerami (Maserati) remained first in 32m.04s, followed by Matrullo (Maserati) 32m.29s, Pratesi (Salmson) 33m.34s and Ruggeri (Maserati) 33m.56s. On the third lap Nuvolari established a new record lap of 13m.42.2s at an average speed of 87.570 km/h, which improved upon last year's record of 14m.00.6s at 85.652 km/h, made by Varzi in his Bugatti. Borzacchini followed not far behind and Campari drove his usual steady race. Gazzabini was a slow driver, so it is not surprising that he was not mentioned in the reports. The order after three laps was: 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) (41m.29s); 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) (41m.37s); 3. Varzi (Bugatti) (42m.06s); 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) (42m.30s); 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) (42m.46s); 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) (43m.55s); 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) (43m.59s); 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) (44m.30s); 9. Biondetti (M-B Speciale) (47m.10s); 10. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) (47m.37s); 11. Castelbarco (Maserati) (47m.39s); 12. Corsi (Maserati) (50m.32s); 13. Rondina (OM) (52m.00s); 14. Fontana (Alfa Romeo) (52m.49s). In the 1100 cc class Cerami (Maserati) 47m.58s was still in the lead, followed by Matrullo (Maserati) 48m.43s and Del Re (Fiat) 53m.25s. Cambi's Salmson retired with a broken oil pipe. After four laps the Nuvolari-Varzi duel had changed to one between Nuvolari and Borzacchini. "Nivola" completed another lap in 13m.45s, which was equaled by Borzacchini. Varzi still held third place but was no match to the Alfa monoposti. Taruffi was still matching the pace of Campari. The standings were: 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 55m.14s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 55m.22s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 56m.03s; 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 56m.33s; 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) 56m.52s; In the small car class Cerami (Maserati) remained first with 1h.04m, followed by Matrullo (Maserati) 1h.05m, Pratesi (Salmson) 1h.06m.50s, Del Re (Fiat) 1h.11m.31s and Ruggeri (Maserati) 1h.16m.46s. On lap five Nuvolari was still leading Borzacchini but only by nine seconds, then came Varzi in third place but already over one minute behind Nivola, followed by Campari, Taruffi, Ghersi, Brivio and D'Ippolito. Perhaps the highlight of this race was the battle between Ghersi and Brivio for 6th and 7th places. After the first lap Ghersi was eight seconds ahead, but Brivio reduced this consistently to seven seconds on lap two, four seconds a lap later and after five laps they were only two seconds apart. The order after five laps was: 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.08m.59s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 1h.09m.08s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 1h.10m.00s; 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.10m.36s; 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) 1h.11m.04s; 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) 1h.12m.55s; 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) 1h.12m.57s; 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) 1h.14m.00s; 9. Biondetti (M-B Speciale) 1h.18m.00s; 10. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) 1h.18m.42s; 11. Castelbarco (Maserati) 1h.19m.58s; 12. Corsi (Maserati) 1h.23m.57s; 13. Rondina (OM) 1h.25m.25s; 14. Fontana (Alfa Romeo) 1h.23m.25s; In the small car classification Cerami (Maserati) led in 1h.19m.59s, followed by Matrullo (Maserati) 1h.21m.05s, Pratesi (Salmson) 1h.23m.26s, Del Re (Fiat) 1h.29m.40s and Ruggeri retired his Maserati. After six laps Nuvolari's advantage stayed at nine seconds, while the gap between Varzi and Campari lessened. Finally, after more than 100 kilometers of racing Brivio fell back a little, but was still only nine seconds behind Ghersi. Fontana retired due to mechanical troubles. 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.22m.46s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 1h.22m.55s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 1h.24m.05s; 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.24m.33s; 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) 1h.25m.07s; 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) 1h.27m.10s; 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) 1h.27m.19s; 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) 1h.28m.36s; 9. Biondetti (M-B Speciale) 1h.33m.08s; 10. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) 1h.34m.25s; 11. Castelbarco (Maserati) 1h.35m.48s; 12. Corsi (Maserati) 1h.40m.52s; 13. Rondina (OM) 1h.42m.07s; The order in the 1100 cc car class was Cerami (Maserati) 1h.35m.58s, Matrullo (Maserati) 1h.37m.26s, Pratesi (Salmson) 1h.40m.04s and in fourth place Del Re (Fiat) in 1h.48m.07s. On lap seven Borzacchini slowed down a bit and so did Nuvolari. The gap which had been a scant nine seconds increased marginally to 13, so Borzacchini was hardly out of contention. Biondetti, who was expected to have a good race, was once more unlucky, as he broke a wheel-hub of his Bugatti and retired. 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.36m.40s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 1h.36m.53s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 1h.38m.11s; 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.38m.36s; 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) 1h.39m.18s; 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) 1h.41m.37s; 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) 1h.41m.47s; 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) 1h.43m.25s; 9. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) 1h.49m.58s; 10. Castelbarco (Maserati) 1h.52m.17s; 11. Corsi (Maserati) 1h.57m.40s; 12. Rondina (OM) 2h.03m.51s; Cerami (Maserati) led the 1100 cc class in 1h.52m.08s, pursued by Matrullo (Maserati) 1h.53m.48s, Pratesi (Salmson) 1h.56m.04s and Del Re (Fiat) in 2h.06m.08s. On lap eight Varzi drove a lap in 13m57s, maintaining his advantage over Campari. Borzacchini drove a slightly faster lap than Nuvolari. At the same time Brivio cut into Ghersi's lead by three seconds and was now only seven seconds behind. The order remained the same. 1. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.50m.42s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 1h.50m.54s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 1h52m08s; 4. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 1h.52m.36s; 5. Taruffi (Alfa Romeo) 1h.53m.42s; 6. Ghersi (Bugatti) 1h.56m.14s; 7. Brivio (Alfa Romeo) 1h.56m.21s; 8. D’Ippolito (Alfa Romeo) 1h.58m.14s; 9. Balestrero (Alfa Romeo) 2h.05m.22s; 10. Castelbarco (Maserati) 2h.08m.15s; 11. Corsi (Maserati) 2h.17m.07s; 12. Rondina (O.M.) 2h.20m.21s; The eighth lap concluded the dull race of the 1100 cc class without any changes in a boring procession. Cerami was victorious, ahead of Matrullo, Pratesi and Del Re. On lap nine the order was still Nuvolari, Borzacchini, Varzi, Campari, Taruffi, Ghersi, Brivio and D'Ippolito. Nuvolari increased his advantage to 26 seconds from Borzacchini, who was 1m.43s ahead of the steadily driving Varzi in third place. The opinion of the press was that Campari was attacking Varzi. But on lap nine Varzi had actually started to slow down, losing precious seconds from the advantage he had kept over Campari. This enabled the regularly driving Campari, who kept his lap times just around the 14 minutes mark, to come closer to Varzi. Ghersi was now only three seconds ahead of Brivio. These minor changes brought a little excitement near the end of an otherwise lackluster race. 1. Nuvolari (Alfa R.) 2h.04m.16s; 2. Borzacchini (Alfa R.) 2h.04m.42s; 3. Varzi (Bugatti) 2h.06m.25s; 4. Campari (Alfa R.) 2h.06m.37s. At the end of the tenth lap Nuvolari became the celebrated victor with Borzacchini in second place, followed by Campari. The opinion had persisted that Campari was attacking Varzi, while in fact Varzi had slowed down even more on lap ten, which enabled Campari to advance to third place on the very last lap. Varzi in fact crossed the line first, not having been passed on the road throughout the entire race, but since he had started three minutes before Nuvolari, victory went to the latter as he roared over the finishing line about one minute later. Taruffi, fastest of the Scuderia Ferrari drivers, was happy with his performance in fifth place ahead of teammates Ghersi, Brivio and D'Ippolito. Results 1°(N°30) Tazio Nuvolari, Alfa Romeo B/P3 -2600cc (10 Laps) 2h.18m.19.4s; 2°(N°36) Mario U. Borzacchini, Alfa Romeo B/P3 -2600 (10 Laps) 2h.18m.45.0s; 3°(N°26) Giuseppe Campari, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.20m.38.0s; 4°(N°4) Achille Varzi, Bugatti T51 2300cc (10 Laps 2h.20m.52.0s; 5°(N°34) Piero Taruffi, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.24m.30.0s; 6°(N°42) Pietro Ghersi, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.24m.55.0s; 7°(N°46) Antonio Brivio, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.24m.56.0s; 8°(N°44) Guido D'Ippolito, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.27m.44.0s; 9°(N°16) Renato Balestrero, Alfa Romeo Monza -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.38m.57.0s; 10°(N°10) Luigi Castelbarco, Maserati 26M -2500cc (10 Laps) 2h.39m.45.0s; DNC(N°6) Silvio Rondina, OM 665 -2200cc (9 Laps) flagged off; DNC(N°2) Secondo Corsi, Maserati 26 -1500cc (9 Laps) flagged off; DNF(N°8) Clemente Biondetti, MB Speciale -2500cc (7 Laps) broken wheel hub; DNF(N°12) Eugenio Fontana, Alfa Romeo Monza 2300cc (6 Laps); DNF(N°14) Vittoria Orsini, Maserati 26 -1500cc (3 Laps); DNF(N°50) Luigi Premoli, PBM 3000cc (1Laps) crash, overturned; DNF(N°18) Carlo Gazzabini, Alfa Romeo Monza 2300cc (? Laps); Fastest lap: Tazio Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) on lap 3 in 13m.42.2s = 87.6 km/h (54.4 mph). Winner's medium speed: 86.8 km/h (53.9 mph). Weather: sunny and hot. Class up to 1100 cc 1°(N°60) Domenico Cerami, Maserati 4CM -1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.08m.29s; 2°(N°64) Francesco Matrullo, Maserati 4CM -1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.10m.01s; 3°(N°74) Albino Pratesi, Salmson 1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.13m.33s; 4°(N°62) Luigi Del Re, Fiat-Lombard AL3 -1100 (8 Laps) 2h.24m.24s; DNF(N°82) Amedeo Ruggeri, Maserati 26C -1100 (5 Laps); DNF(N°78) Cambi, Salmson 1100 (5 Laps) oil pipe. Fastest lap: Domenico Cerami (Maserati) on lap 3 in 15m.53.8s = 75.5 km/h (46.9 mph) Winner's medium speed: 74.7 km/h (46.4 mph). Weather: sunny and hot. Footnote 1. Compiling the starting grid: The first three rows and fifth row are correct with the help of three photographs. Four drivers, two each in row 4 and 6 could not be placed at their proper grid position. After lengthy investigation the following is a likely scenario but cannot be proven correct. Row 4 might have included #42 Ghersi and #46 Brivio (both likely in the same row). Row 6 might have consisted of #44 D'Ippolito and #50 Premoli. Primary sources researched for this article: - AUTOMOBIL-REVUE, Bern - AZ - Motorwelt, Brno - CORRIERE DEL TIRRENO, Livorno - IL LITTORIALE, Roma - IL TELEGRAFO, Livorno - L'Auto Italiana, Milano - Manifesto by the Royal AC of Italy & Moto Club Livorno - Motor Sport, London (by Hans Etzrodt in: The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing) |

|

|

|

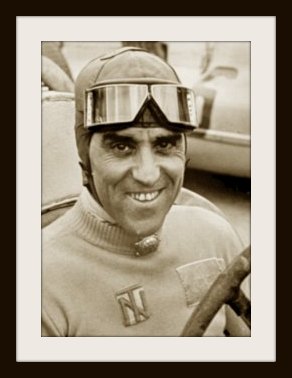

TAZIO NUVOLARI Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari (November 16, 1892 – August 11, 1953) was an Italian motorcycle and racecar driver, known as “Il Mantovano Volante” (The Flying Mantuan) or Nivola. He was the 1932 European Champion in Grand Prix motor racing. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche called Nuvolari “The greatest driver of the past, the present, and the future”. Tazio Nuvolari started out in motorcycle racing in 1920 at the age of 27. In 1925 he captured the 350cc European Championship. From then until the end of 1930, he competed both in motorcycle racing and in automobile racing. For 1931, he decided to concentrate fully on racing cars and agreed to race for Alfa Romeo's factory team, Alfa Corse. In 1932 he took two wins and a second place in the three European Championship Grands Prix, winning him the title. He won four other Grands Prix including a second Targa Florio and the Monaco Grand Prix.After Alfa Romeo officially left Grand Prix racing, Nuvolari stayed on with Scuderia Ferrari who ran the Alfa Romeo cars on a semi-official basis. During 1933, Nuvolari left the team for Maserati after becoming frustrated with the Alfa Romeo's performance. At the end of 1934, Maserati pulled out of Grand Prix racing and Nuvolari returned to Ferrari, who were reluctant to take him back, but were persuaded by Mussolini, the Italian prime minister. The relationship with Ferrari turned sour during 1937, and Nuvolari raced an Auto Union as a one-off in the Swiss Grand Prix that year before agreeing to race for them for the 1938 season. Nuvolari remained at Auto Union until Grand Prix racing was put on hiatus by World War II. The only major European Grand Prix he never won was the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix. Upon his return to racing after the war, he was 54 and suffering from ill health. His final race, in 1950, saw him finish first in class and fifth overall. He died in 1953 from a stroke. Personal and early life Nuvolari was born in Castel d'Ario near Mantua on 16 November 1892 to Arturo Nuvolari and his wife Elisa Zorzi. The family were well acquainted with motor racing as Arturo and his brother Giuseppe were both bicycle racers - Giuseppe was a multiple winner of the Italian national championship and was particularly admired by a young Tazio. Nuvolari was married to Carolina Perina, and together they had two children: Giorgio (born 4 September 1918), who died in 1937 aged 19 from myocarditis, and Alberto, who died in 1946 aged 18 from nephritis. Career: Motorcycle racing. Nuvolari gained his license for motorcycle racing in 1915 at the age of 23. His motorcycling career was postponed, however, by the outbreak of World War I and Nuvolari served as a driver in the Italian army. Once the war had ended, he resumed his sporting career and took part in his first race at the Circuito Internazionale Motoristico in Cremona in 1920. During this period, Nuvolari also dabbled in car racing, winning a reliability trial in 1921. In 1925, Nuvolari became the 350 cc European Motorcycling champion by winning the European Grand Prix. At the time, the European Grand Prix was considered the most important race of the motorcycling season and the winners in each category were designated European Champions. Nuvolari also won the Nations Grand Prix four times between 1925 and 1928 and the Lario Circuit race five times between 1925 and 1929, all in the 350 cc class and each time on a Bianchi motorcycle. It was also in 1925 that Nuvolari was asked by Alfa Romeo to have a trial in their Grand Prix car. The car's gearbox seized and Nuvolari crashed, severely lacerating his back. Despite his injuries, he competed in the Nations Grand Prix at Monza six days later, winning the race after he had persuaded staff at the hospital to bandage him in a manner such that he could sit on his motorcycle and receive a push start. A switch to four wheels. 1931-1932: Alfa Corse Coppa Consuma 1930, Tazio Nuvolari driving Alfa Romeo 6C1750GS. In 1930, Nuvolari won his first RAC Tourist Trophy (he won one more time in 1933). According to a legend, when one of the drivers broke the window of a butchery, Nuvolari, when passing by it, drove on the pavement and tried to catch a ham. According to Sammy Davis who met him there, Nuvolari showed a great sense for dark humour and seemed to enjoy situations when everything went wrong. For example, he told Enzo Ferrari after he got a ticket for a journey home from the Sicilian Targa Florio "What a strange businessman you are. What if I am brought back in a coffin?" Nuvolari and his co-driver Battista Guidotti in Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 GS spider Zagato won the Mille Miglia, becoming the first to complete the race at an average speed of over 100 km/h (62 mph). Due to starting after his team-mate Achille Varzi, he was leading the race despite still being behind Varzi on the road. In the dark of night Nuvolari tailed Varzi for tens of kilometres, riding at speed of 150 km/h (93 mph) with his headlights off, thereby being invisible in Varzi's rear-view mirrors; he then switched on his headlights before overtaking "the shocked" Varzi near the finish at Brescia. 1931 Towards the end of 1930, Nuvolari made a decision to stop racing motorcycles and to concentrate fully on car racing during 1931. The new season saw a change in the regulations which meant that Grand Prix races had to be at least 10 hours in duration. After drawing ninth place on the grid at the Italian Grand Prix, Nuvolari started the race in an Alfa Romeo shared with Baconin Borzacchini. However, the car had to retire with mechanical problems after 33 laps. Nuvolari then teamed up with Giuseppe Campari and the pair took the race win, although Nuvolari could not receive the championship points from it. Apart from a second place at the Belgian Grand Prix, the only other European Championship race, the French Grand Prix, resulted in a disappointing 11th place finish. Aside from the main European Championship Grands Prix, Nuvolari took victories in the Targa Florio and the Coppa Ciano. 1932 1932 saw a revision of the previous year's regulation change, with the race duration being reduced to between five and ten hours. The season was the only one in which Nuvolari regularly had one of the fastest cars, the Alfa Romeo P3. A consequence was that in the three European Championship Grands Prix, he took two wins and a second place - winning the championship by four points from Borzacchini. He took four other wins during the season, including the prestigious Monaco Grand Prix and a second Targa Florio. His mechanic Mabelli said about this race: "Before the start, Nuvolari told me to go down on the floor of the car everytime he shouts, which was a signal that he went to a curve too fast and that we need to decrease the car´s center of mass. I spent the whole race on the floor. Nuvolari started to shout in the first curve and wouldn't stop until the last one." On 28 April that year he was given a golden turtle badge by the famous Italian writer Gabriele d'Annunzio which symbolised the opposite of his speed. He wore the turtle ever since and it became his talisman and also his symbol. 1933-1937: Scuderia Ferrari and Maserati “Tazio Nuvolari was not simply a racing driver. To Italy he became an idol, a demi-god, a legend, epitomising all that young Italy aspired to be; the man who “did the impossible”, not once but habitually, the David who slew the Goliaths in the great sport of motor racing. He was Il Maestro.” 1933 The 1933 season was the first year of a two year hiatus for the European Championship, and saw Alfa Romeo stop their official involvement in Grand Prix racing. They did not disappear altogether as they were represented by Enzo Ferrari's privateer effort. For economic reasons, the P3 was not passed on to Ferrari and they were forced to use the Monza, the predecessor of the P3. Maserati were their main opposition with a highly improved car. Nuvolari is often reported as having been involved in a race-fixing scandal at the Tripoli Grand Prix. It is said he, along with Achille Varzi and Baconin Borzacchini, conspired to fix the race in order to profit from the Libyan state lottery. The lottery saw 30 tickets drawn before the race - one for each starter - and the holder of the ticket corresponding to the winning driver would win seven and a half million lire. However, this story is said by some to be a work of fiction by Alfred Neubauer, the team manager of Mercedes-Benz at the time and a well-known raconteur with a penchant for spicing up a story. Some of the facts in Neubauer's version do not hold true with documented records of events, which point to Nuvolari, Varzi and Borzacchini agreeing to pool the prize money should one of them win, as opposed to Neubauer's claims of race fixing. Alfa Romeo announced that for the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Nuvolari would be competing in a team with Raymond Sommer. Sommer argued that he would be drive the majority of the race as he was more familiar with the circuit and Nuvolari would likely break the car. Nuvolari countered that he was a leading Grand Prix driver and Le Mans was a simple layout that would not trouble him, to which Sommer backed down and they agreed to divide the driving equally. The race itself saw Sommer and Nuvolari take a two lap lead before their fuel tank developed a hole, which was plugged by chewing gum whilst in the pits. Several more pit stops were necessary as the makeshift repair came undone several times during the race. Nuvolari drove from then until the end of the race, breaking the lap record nine times and winning the race by approximately 400 yards (366 m). 1934 "Let any who say it was foolhardy at least be honest and admit it was one of the finest exhibitions of pluck and grit ever seen. By such men are victories won!" Earl Howe, on Nuvolari's drive in the 1934 AVUS-Rennen whilst having one leg in plaster At the start of 1934, Nuvolari entered the Monaco Grand Prix in a privately owned Bugatti. Having made it up to third place in the race, he suffered brake troubles and fell back to fifth at the finish, two laps behind the winner, Guy Moll. Whilst racing at Alessandria in the Circuito di Pietro Bordino race, Nuvolari crashed whilst avoiding Carlo Felice Trossi's stricken car. He broke a leg, but suffering from boredom in hospital, he decided to enter the AVUS-Rennen just over four weeks after his accident. His Maserati was specially modified so that he could use all three of its pedals with his left foot; his right was still in plaster. Troubled by cramp, Nuvolari finished fifth. By the time of the Penya Rhin Grand Prix in late June, Nuvolari's leg was finally out of plaster, but was still causing him troubles as he battled pain until he retired his Maserati with technical problems. In the Italian Grand Prix, Nuvolari debuted Maserati's new 6C-34 model. The car performed poorly and Nuvolari could only finish fifth, three laps behind the Mercedes-Benz of Rudolf Caracciola and Luigi Fagioli. 1935 For 1935, Nuvolari set his sights on a drive with the German Auto Union team. The team were lacking top-line drivers, but relented to pressure from Achille Varzi who did not want to be in the same teams as Nuvolari. Nuvolari then approached Enzo Ferrari, but was turned down as he had previously walked out on the team. However, Mussolini, the Italian prime minister, intervened and Ferrari backed down. In this year, Nuvolari scored his most impressive victory, thought by many to be the greatest victory in car racing of all times, when at the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, driving an old Alfa Romeo P3 (3167 cm³, compressor, 265HP) versus the dominant, all conquering home team's cars of five Mercedes Benz W25 (3990 cm³, 8C, compressor, 375 hp (280 kW), driven by Caracciola, Fagioli, Hermann Lang, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Geyer) and four Auto Union Tipo B (4950 cm³, 16C, compressor, 375 hp (280 kW), driven by Bernd Rosemeyer, Varzi, Hans Stuck and Paul Pietsch). This victory is known as “The Impossible Victory”. The crowd of 300,000 applauded Nuvolari, but the representatives of the Third Reich were enraged. 1936 Nuvolari had a big accident in May during practice for the Tripoli Grand Prix and it is alleged that he broke some vertebrae. Despite a limp, he took part in the race the following day and finished eighth. 1937 At the beginning of 1937, Alfa Romeo took their works team back from Ferrari and entered it as part of the Alfa Corse team. Nuvolari stayed with Alfa Romeo despite becoming increasingly frustrated with the poor build quality of their racing cars. At the Coppa Acerbo, Alfa Romeo's new 12C-37 car proved to be slow and unreliable. This frustrated Nuvolari, who handed his car over to Giuseppe Farina mid-race. Not wanting to leave Alfa Romeo, he drove an Auto Union in the Swiss Grand Prix as a one-off. After the Italian Grand Prix, Alfa Romeo withdrew from racing for the remainder of the season and dismissed Vittorio Jano, their chief designer. 1938 Although Nuvolari started 1938 as an Alfa Romeo driver, a split fuel tank in the first race of the season at Pau was enough for him to walk out on the team, critical of the poor workmanship that was exhibited. He announced his retirement from Grand Prix racing and took a holiday in America. At the same time, Auto Union were having to rely on inexperienced drivers. Following the Tripoli Grand Prix they contacted Nuvolari who, having been refreshed from his break, agreed to drive for them. Post-war racing In 1946, Nuvolari raced in the Milan Grand Prix using only one hand to steer; the other was holding a bloodstained handkerchief over his mouth. Nuvolari's last race was in 1950 at the Palermo-Montepellegrino hillclimb, in which he came first in his class and fifth overall. Death and legacy Nuvolari never formally announced his retirement, but his health had deteriorated and he became increasingly solitary. In 1952 he suffered a stroke which left him partially paralysed, and he died in bed a year later from a second stroke. Almost the entire town of Mantua attended his funeral, which is said to have seen an attendance of between 25 and 55 thousand people. The funeral procession was a mile long, and Nuvolari's coffin was placed on a car chassis which was pushed by Alberto Ascari, Luigi Villoresi and Juan Manuel Fangio. Nuvolari has had four cars named after him - the Cisitalia 202 spider "Nuvolari", the Alfa Romeo Nuvola, the EAM Nuvolari S1, and the Audi Nuvolari Quattro. Nuvolari was one of the early proponents (if not the inventor, according to Enzo Ferrari) of the four-wheel drift technique. The technique was later utilised by drivers such as Stirling Moss. In 1976, Italian singer-songwriter Lucio Dalla wrote the song Nuvolari celebrating his myth. The song is still very famous in Italy, and it's part of Dalla's album Automobili (Cars). An Italian pay-TV channel dedicated to motor sports is also named Nuvolari. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

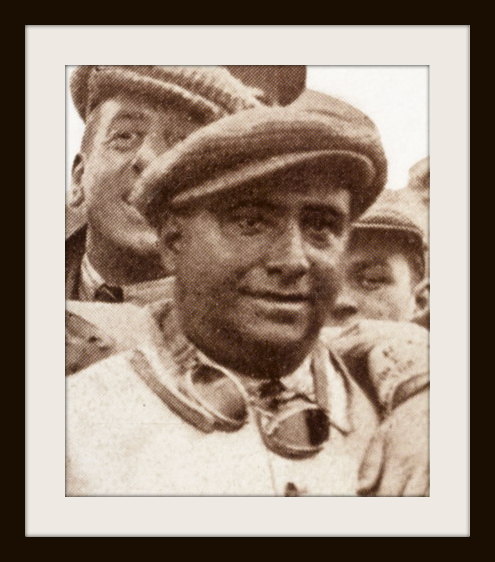

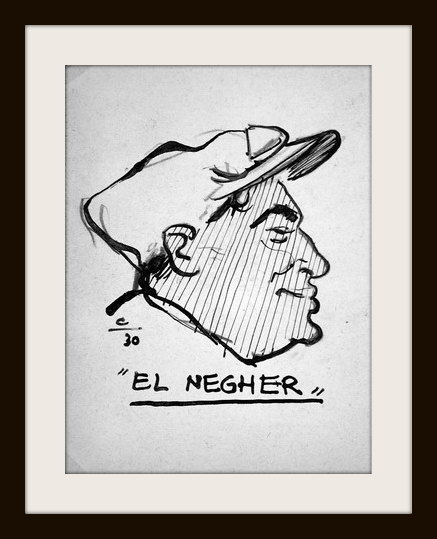

GIUSEPPE CAMPARI QUANDO CANTAVA IL NEGRO DI LODI Pomeriggio del 10 settembre 1933, Autodromo di Monza. Si è già svolto in mattinata il Gran Premio d’Italia, e ora si stanno preparando i concorrenti per il Gran Premio di Monza, che prevede tre batterie di 14 giri di pista ciascuna, per complessivi 63 km, ed una finale di 22 giri (99 km) alla quale saranno ammessi i primi quattro classificati di ogni batteria. Dei dieci iscritti alla prima batteria, se ne avviano alla linea di partenza soltanto otto: Trossi sull’attesissima Duesenberg, iscritta dalla Scuderia Ferrari, Premoli su MBP (sigla che sta per Maserati-Bugatti-Premoli), Straight su Maserati, Moll, Pages e Bonetto su Alfa Romeo, Czaykowski e Battilana su Bugatti. Nuvolari (Maserati) e Siena (Alfa Romeo), troppo provati dalla gara del mattino, hanno dato forfait. Alle 14,10 in punto S.E. Starace da’ il via, Premoli, Straight e Trossi balzano in testa, mentre Pages alla prima curva finisce direttamente fuori strada, fortunatamente senza danni. I giri si susseguono, il pilota francese conte Czaykowski, d’origine polacca, alla sua prima gara in Italia, passa al comando. Al settimo giro Trossi giunge rallentando e si ritira. Si saprà poi che per avaria ad un pistone il carter del motore si era sfondato, inondando d’olio l’imbocco della curva sud. Non sembra un evento di fondamentale importanza: il pilota non si è fatto niente, la gara è proseguita indisturbata, e si è conclusa con la vittoria di Czaykowski, mentre il giro più veloce l’ha compiuto il giovanissimo Moll. Finita la prima batteria, contemporaneamente all’arrivo di S.A.R. il Principe Umberto, una vettura chiusa si avvia sulla pista con una lunga scopa sporgente dal finestrino. Gli organizzatori con questo espediente intendono eliminare l’olio uscito dalla Duesenberg di Trossi: dopo la scopa (che non sembra a priori il mezzo migliore per spazzare via un liquido vischioso da una superficie) viene anche sparsa sul luogo della sabbia. Qualche minuto dopo arrivano i concorrenti della seconda batteria. Campari, su Alfa Romeo, e Borzacchini, su Maserati, sono molto applauditi, quasi quanto la signorina Helle Nice, compagna di squadra di Campari. Si allineano alla partenza anche Balestrero, Barbieri, Castelbarco e Pellegrini, tutti su Alfa Romeo. Alle 15 precise Starace da’ il via. Balzano in testa Campari, Borzacchini e Barbieri. Spariscono rombando dalla curva nord e il pubblico, tutto insieme, si volge a guardare dal lato opposto aspettandosi di vederli comparire dalla curva sud. Però non succede niente. Appare il solo Balestrero, seguito da Pellegrini e poco dopo dalla Helle Nice. Quindi, nessuno. L’attesa si fa via via spasmodica, poi ricompaiono Balestrero e gli altri due, facendo il segno di qualcuno che si è rovesciato. Gli addetti al posto di soccorso alla curvetta del circuito stradale si avviano di corsa verso la curva sud della pista. Da altre parti, lontano, sui prati, si vedono persone accorrere: spettatori, qualche milite. Balestrero ripassa per la terza volta e quasi si ferma davanti alla cabina dei cronometristi. Lo si vede gesticolare vivacemente, e ripartire con un gesto di disperazione. Rallenta quindi anche davanti ai box, pressato dai suoi che chiedono notizie. E quindi, con gli altri due piloti, riprende la corsa, continuando regolarmente, come schiavi alla catena, i previsti 14 giri. La stessa Helle Nice, impietrita al volante come una statua, continua a correre, passando e ripassando per quella stessa tragica curva. Tragica davvero, perché, ormai la voce si è sparsa di bocca in bocca, in essa hanno trovato la morte i due campioni italiani, Campari e Borzacchini, uno sul colpo, l’altro venti minuti dopo all’Ospedale di Monza. E mentre il pubblico fischia e smania per avere notizie, non volendo credere ad una tragedia così immane, l’altoparlante, con una colossale mancanza di tatto, si affanna per far interessare la folla alla sorte del settenne Tognasso, prima perduto poi ritrovato dagli ansiosi e distratti genitori. Il pubblico viene addirittura invitato a “non credere alle voci correnti non autorizzate”. Nonostante gli sforzi degli organizzatori però, per quella consueta inspiegabile comunicazione a tam tam, tutti sanno tutto, e l’incidente occorso comincia a delinearsi con spaventosa chiarezza. Appena dopo la partenza i corridori si erano divisi in due gruppi. In testa Campari e Borzacchini, seguiti a brevissima distanza da Castelbarco e da Barbieri, e quindi dagli altri tre. La gara si svolgeva sulla pista che è costituita da due rettilinei congiunti da due ampie curve rialzate, la prima a nord appena finito il rettilineo del traguardo, la seconda a sud terminante sullo stesso rettilineo. Appena all’inizio della curva sud, pressappoco dove si era sparso l’olio della Duesenberg, Campari, che in quel momento era sulla destra, si porta sulla sinistra, verso il rialzo della curva, arrivando ad un soffio dall’investire a folle velocità il semaforo n. 15. Tenta forse una sterzata in extremis, ma rimane per un buon tratto sull’orlo della pista. Traccia di questo passaggio al limite rimane nel blocco di cemento demolito, dopodiché la rovinosa caduta dalla scarpata nel fossato sottostante. Borzacchini, che per tentare di sorpassare Campari doveva tenersi necessariamente sulla sinistra, si vede chiudere la strada proprio dal compagno, e nel tentativo disperato di evitarlo perde il controllo della vettura e vola oltre il prato. Terzo sopraggiunto, Castelbarco, stesso copione: l’arrivo in velocità, il tentativo di sterzo in curva, la perdita di controllo della macchina, il volo fuori strada. Solamente Barbieri, quarto coinvolto nell’incidente, riesce a tenersi a destra e a uscire di strada meno catastroficamente, essendo da quel lato il prato allo stesso livello della pista. Gli altri tre, Balestrero, Pellegrini ed Helle Nice, come abbiamo visto continuano la corsa, anzi il secondo giro dopo la tragedia Balestrero fa registrare la velocità più alta (179,428 km/h). Intanto gli accorsi cercano di rianimare Campari, trovato schiacciato sotto la macchina capovolta, ma è inutile. Borzacchini da’ segni di vita, ed è portato immediatamente all’Ospedale di Monza, dove spira dopo poco, per schiacciamento del torace, frattura della colonna vertebrale ed emorragia interna. Castelbarco non si è invece fatto quasi nulla: solo una ferita al mento subito medicata, tanto da recarsi egli stesso alla radio e rassicurare direttamente il pubblico sulla sua sorte. Questa comunicazione non fa che indispettire maggiormente gli spettatori, che continuano a non avere ricevuto alcuna comunicazione ufficiale sul destino dei due campioni. Fino alla fine della gara infatti non viene detta nemmeno una parola. I fischi diventano assordanti quando lo speaker, come se nulla fosse, esorta il pubblico a non invadere la pista “per evitare che si verifichino inutili disgrazie”. L’espressione, con due morti sulla pista, pare, ed è, davvero infelice. Finita la seconda batteria con la vittoria di Balestrero, dovrebbe partire la terza batteria. Passano i minuti, passa mezz’ora, poi un’ora, senza che nulla succeda. Poi si vedono cinque concorrenti (Ghersi su Bugatti, Biondetti su Maserati, Cornaggia su Alfa Romeo, Lord Howe su Bugatti e Lehoux su Bugatti) allinearsi al traguardo. Ma ancora non partono. Addirittura ad un dato momento lasciano le macchine e si avviano a piedi verso gli Uffici della Direzione dell’Autodromo. Si saprà in un secondo tempo che, a scanso di contestazioni, gli organizzatori fanno loro firmare una dichiarazione in cui si attesta la loro volontà di continuare la gara nonostante l’incidente di poco prima. E finalmente, con un’ora e dieci di ritardo, è data la partenza. L’incubo sembra ricominciare quando Ghersi al sesto giro fa un testa coda nel solito posto della curva. Fortunatamente riprende il controllo e finisce addirittura secondo, dopo Lehoux. Infine, per le 18, è fissata la finale di questa gara che sembra interminabile, verso cui nessuno ha più interesse ma che ci si condanna a voler concludere. Si allineano alla partenza Straight, Moll, Bonetto, Czaykowski, Biondetti, Balestrero, Helle Nice, Ghersi, Lehoux, Pellegrini e Cornaggia. La lotta per la vittoria, si capisce fin dai primi giri, è tra Lehoux e il conte polacco, e continua acerrima fino all’ottavo giro quando passa Lehoux che davanti a box fa un gesto che fa accapponare la pelle a tutti gli astanti. E’ lo stesso gesto con cui Balestrero tentava di far capire che vi erano delle macchine capottate. Difatti, dal luogo della solita, sinistra, maledetta curva sud, si eleva una colonna di fumo nero. E’ Czaykowski, stavolta, che ha sbandato. La vettura si è rovesciata, incendiata, ribaltata ancora precipitando dalla scarpata. Per il pilota, imprigionato nella vettura in fiamme, non c’è più niente da fare. Neanche di quest’ultima tragedia viene data ufficiale comunicazione, ma si decide di ridurre il percorso a 14 giri, anziché i 22 previsti dal regolamento. Lehoux vince, tra l’indifferenza dei più, la costernazione di pochi. Il R.A.C.I., organizzatore della gara, diramò nei giorni successivi un comunicato ufficiale, che diceva: “Gli incidenti verificatisi al circuito di Monza durante il VI Gran Premio di Monza, e precisamente durante la seconda batteria e la finale della gara, secondo una prima indagine sono dovuti tutti e tre ad eccesso di velocità con le conseguenze derivanti dalla impossibilità di tenere la curva, la quale consente velocità fino ad un certo punto e non tutte le velocità”. E quindi proseguiva aggiungendo: “Può avere contribuito a rendere più difficile un altro elemento, quello cioè dell’umidità della pista tenuto conto dell’acqua venuta giù ad intermittenza. Da qualche spettatore si è accennato anche alla possibilità che l’incidente possa essere dipeso da eventuale spargimento di olio da una macchina che aveva corso nella precedente batteria – da notarsi l’attribuzione ad un anonimo spettatore, ossia ad un elemento insignificante dal punto di vista tecnico, di una ipotesi più che fondata – Tale versione è esclusa dal fatto che gli incidenti si sono verificati, seppure nelle vicinanze, alcuni metri fuori dalla zona dove l’olio è stato rilevato, e dalla considerazione che le altre macchine partecipanti alla gara hanno continuato e finito la gara stessa ripassando tutte le volte sul medesimo tratto senza inconveniente alcuno”. Insomma signori, la situazione è chiara: se si fossero ammazzati tutti e venti i concorrenti a distanza millimetrica l’uno dall’altro, se ne poteva parlare, ma così…è chiaro che è stata una fatalità. La Procura del Re di Milano istituì un’istruttoria sui fatti. Vennero nominati tre periti tecnici nelle persone degli ingegneri Filippo Tajani, Piero Benzi e Mario Ferraris i quali presentarono all’inizio di ottobre la loro perizia collegiale. Conclusioni: non potersi procedere contro alcun responsabile, per assoluta mancanza di elementi di colpa. Gli incidenti erano avvenuti in seguito alle mutate condizioni della pista, tali da non consentire – specialmente nel punto dove la triplice sciagura si produsse – le più elevate velocità alle quali presumibilmente si spinsero i disgraziati corridori, vittime del loro ardimento. Perciò, chi è causa del suo mal pianga se stesso. Il più illustre dei tre caduti era sicuramente Giuseppe Campari, un gigante buono, sperimentato e valentissimo pilota Alfa Romeo, che vantava al suo attivo più di trenta vittorie assolute, alcune delle quali di assoluto prestigio anche internazionale, due titoli di Campione Italiano (1928 e 1931), un’affermazione di qualche settimana prima al Gran Premio di Francia a Monthléry che ne aveva rinverdito l’immagine di grande pilota. Un personaggio imponente, innanzitutto per la mole, per lo stile di guida, più vicino a quello di Lancia (a cui lo accomunava il fisico poderoso) che a quello elegante e preciso di Nazzaro, per il carattere gioviale e compagnone. Ma per tutta la vita fu come sottovalutato, meno considerato dei suoi avversari, come Antonio Ascari, o Tazio Nuvolari, a cui non era certo inferiore. Forse contribuì la sua bonarietà, la sua consapevolezza di venire dal popolo, di non sapersi comportare al cospetto delle autorità, di mancare di educazione (il che non era vero) o di istruzione. In realtà fu un grandissimo corridore perché tra i pochi a possedere un bagaglio tecnico invidiabile, avendo sviluppato le sue capacità di pilota grazie ad un lungo tirocinio da collaudatore. Nutriva molte altre passioni, oltre alle corse: per il bel canto e la lirica, innanzitutto, tanto da aver sposato la cantante Lina Cavalleri, quasi omonima della più celebre Lina Cavalieri, e da esibirsi in pubblico nella Traviata ed altre opere. La stampa automobilistica, alla morte, unì il suo nome a quello delle altre due vittime in necrologi retorici ed altisonanti, ma non vi fu un solo giornalista che ne rievocò la figura e la carriera in articoli successivi all’incidente. Charles Faroux, il più autorevole dei giornalisti automobilistici francesi, l’aveva definito alla vigilia del Gran Premio di Francia del 1933 (vinto proprio da lui) un “vétéran souvent, vainqueur naguère” ossia un veterano che non vince mai. E aveva proseguito sul suo conto aggiungendo impietosamente: “Pour Campari, on peut déjà craindre l’age, parce que c’est une épreuve veritablement athlétique que de mener à toute volée, pendant 500 km, un de ces petits monstres d’acier” (sarebbe meglio che Campari tenesse conto della sua età, perché guidare a folle velocità uno di questi piccoli mostri di acciaio è una prova squisitamente atletica). Lo stesso Ferrari, nel rievocarne la figura nel suo “Piloti che gente” ripercorre episodi che lo mettono in burletta, anche se poi riconosce che “non era soltanto un pilota di eccezionale valore ma anche un combattente indomabile, un uomo che pur di vincere non badava al rischio, come neppure a tanti altri accorgimenti”. E quindi spiega: “Alle prove della Mille Miglia del 1928 ero con lui in macchina al Passo della Raticosa. I nostri sedili erano due semplici baquets, come venivano chiamati a quel tempo, sedili cioè fissati ad un semplice traliccio a sua volta ancorato con filo di ferro e quattro bulloni al telaio. E appunto, dal pavimento di legno, cominciarono a sprigionarsi schizzi che ci arrivarono al volto. Superando l’urlo del motore, gridai a Campari: “Non vorrei che si fosse rotto un manicotto! Fermiamoci a guardare!” Non mi rispose. Lo osservai sbalordito. Che razza d’uomo era, per trascurare un pericolo del genere? Lo osservai da capo a piedi, e così mi accorsi che dalla tuta sempre troppo corta uscivano dal fondo lunghe mutande di percalle, assicurate con una fettuccia alle calze. Ed era proprio da qui che fuoriusciva quel liquido che poi rimbalzando sui vortici d’aria irrorava l’abitacolo. Sgomento, mi rivolsi al mio compagno in milanese, sapendo che a questo avrebbe risposto. “Peppin – urlai – se gh’è?” E lui: “Ohé, te vurrett minga che me fermi intant che sunt in allenament? Bisugna pur allenass a pissass adoss”.Campari era anche questo: certamente non un damerino, grezzo, determinato e testardo. Ma tutt’altro che personaggio farsesco o da macchietta, come invece fu considerato fin troppe volte a cominciare dal soprannome vagamente dispregiativo che gli fu appioppato (“el negher”). La sua biografia ne è evidente prova. Nasce a Lodi l’8 giugno 1892 e a Milano si stabilisce fin da ragazzo. Apre una piccola officina, che abbandona appena l’Alfa Romeo gli offre un posto da meccanico. Nel 1920 si afferma con un’Alfa al Circuito del Mugello, dimostrando ai suoi superiori che in lui non c’è soltanto la stoffa del collaudatore, già molto apprezzato, ma anche quella del pilota. Di questa prima prova l’Alfa non si dimentica. Quando costituisce nel 1923 la sua squadra ufficiale Campari è chiamato a farne parte, insieme ad Antonio Ascari e Ugo Sivocci. Passa un anno, e per Campari arriva la consacrazione più inattesa e straordinaria, che lo pone alla ribalta dello sport automobilistico internazionale: la vittoria al Gran Premio di Francia a Lione (particolare curioso: la sua carriera si apre nel 1924 e si chiude nel 1933 proprio con una vittoria al Gran Premio di Francia). Nel 1925 prosegue la sua carriera di pilota Alfa Romeo, insieme ad Ascari e Gastone Brilli Peri, che si laurea proprio quell’anno vincitore del primo Campionato del Mondo (vedi Auto d’Epoca del dicembre 2000), anche l’affermazione è oscurata dalla morte inaspettata di Ascari sul circuito di Monthléry (vedi Auto d’Epoca del novembre 1995). Il 1926 fu invece l’anno della Bugatti. Ritiratasi temporaneamente l’Alfa Romeo, mutata la formula con la riduzione della cilindrata massima da 2000 a 1500 cc, restano sulla breccia soltanto le francesi Bugatti e Delage, a cui si aggiunge, con scarsa fortuna, l’italiana O.M., con la sua nuova 8 cilindri 1500 sovralimentata. L’Alfa Romeo ritorna alle corse già nel 1927, e difatti Campari si impone d’autorità, ad oltre 104 km/h di media, alla Coppa Acerbo sul circuito dell’Aterno, su un’Alfa 2 litri. Doveva però essere il 1928 l’anno più felice nella vita di Campari. Cominciò trionfando in coppia con Ramponi sulla piccola Alfa 1500, alla Mille Miglia. Con lo stesso modello vince la classe 1500 alla Targa Florio un mese più tardi, quindi conquista il primato sul giro alla media oraria di 175 km/h al Circuito di Cremona e segna il record di 217,6 km/h sui 10 km lanciati. E’ primo assoluto alla Susa Moncenisio, ed è ancora primo assoluto, a quasi 110 km/h, alla Coppa Acerbo, con il giro più veloce ad oltre 121 km orari. Tanto basta per essere proclamato Campione Assoluto d’Italia per il 1928. Il 1929 e il 1930 non furono anni prodighi di successi come i precedenti, anche se nel 1929 Campari si impose nuovamente alla Mille Miglia, di nuovo in coppia con Ramponi, precedendo di dieci minuti il secondo (Morandi-Rosa su O.M.), di dodici minuti i propri compagni di squadra Varzi – Colombo e di un’ora Minoia-Marinoni, anch’essi su Alfa Romeo. Le restanti gare, Targa Florio, circuito del Mugello, circuito del Montenero, per quanto condotte con tenacia e maestria, non lo videro protagonista. Si cominciò addirittura a dire che Campari stesse pensando ad un abbandono dei campi di gara; che avesse accettato una scrittura teatrale che l’avrebbe portato ad esibirsi come cantante nei teatri di Milano, Torino, Genova ed Alessandria. Non c’era molto di vero in queste voci: e difatti Campari non abbandonò affatto le corse. Anzi, intensificò le sue partecipazioni sportive nel 1931, un anno che fu di transizione e incertezza per organizzatori, piloti e costruttori. Infatti, sperimentate le formule del peso e del consumo, l’Associazione Internazionale degli Automobili Clubs decise di adottare una formula libera, prescrivendo solamente la durata massima e minima dei gran premi (non meno di cinque, non più di dieci ore). L’Alfa mise in cantiere una 8 cilindri di 2300 cc, la Bugatti una vettura da 2300 e una seconda da 4900 cc, la Maserati una 1500 e una 2900 a 8 cilindri, la Mercedes una versione migliorata della 7 litri a 6 cilindri. L’Alfa Romeo aveva anche approntato sperimentalmente una 12 cilindri costituita da due motori affiancati di 1750 cc, con compressore, un mostro da 220 cavalli. Al Gran Premio d’Italia di quell’anno Campari, in coppia con Nuvolari, vince con la 8 cilindri, una superba affermazione conseguita a poco meno di 156 km/h. Con la nuova 12 cilindri si impone invece alla Coppa Acerbo sul circuito di Pescara, e arriva secondo assoluto, su Maserati, al Gran Premio d’Irlanda sul circuito di Dublino (gara corsa con un occhio bendato, conseguenza di un sasso che l’aveva colpito in viso). Per la seconda volta, al termine della stagione, Campari é proclamato Campione Assoluto d’Italia. Il 1932 non fu un anno particolarmente fortunato, e non segnò vittorie di rilievo. Sembrò aprirsi con tutt’altro slancio il 1933, con la splendida affermazione sull’autodromo di Monthléry nel Gran Premio di Francia. Ma pochi mesi dopo, al Gran Premio di Monza, la lunga carriera agonistica di Giuseppe Campari terminò. In pochi anni il numero dei piloti italiani di valore internazionale si era paurosamente assottigliato. Per primo era caduto Ascari, nel 1925, poi Masetti, sul circuito delle Madonie, nel 1926, Bordino e Materassi, rispettivamente ad Alessandria e a Monza, nel 1928, Brilli Peri a Tripoli nel 1930, Arcangeli a Monza nel 1931. E ora era stata la volta di Campari e di Borzacchini: otto campioni in otto anni, una strage. E poco importa che Nuvolari, l’unico che abbia desiderato fino all’ultimo di morire in corsa senza riuscirci, fosse solito dire: “I più grandi piloti muoiono in corsa”. Donatella Biffignandi (Per Auto d’Epoca, marzo 2003) GIUSEPPE CAMPARI Giuseppe Campari (June 8, 1892 – September 10, 1933) was an Italian opera singer and Grand Prix motor racing driver. Racing career Born Giuseppe Campari near the city of Lodi southwest of Milan, as a teenager he went to work for the Alfa Romeo automobile company. Campari's job eventually involved test driving factory cars and his skills and interest led to his participation in competitive hillclimbing events. In 1914 the 21-year-old rookie showed his abilities with a fourth place finish at the Targa Florio. Unfortunately, his career was just getting going when World War I broke out and European racing came to a halt. Following the Armistice that ended the war, racing resumed and in 1920 Campari earned his first major race win and the first for the Alfa Romeo company when he drove to victory at Mugello in Tuscany. He repeated as champion at Mugello the next year and took third place at the Targa Florio but did not earn another major championship until he captured the French Grand Prix in 1924 when he was part of a powerful three-man Alfa Romeo team with Count Gastone Brilli-Peri and Antonio Ascari in the P2 cars designed by Vittorio Jano. The 1925 racing season was less than successful for Campari as he and the Alfa Romeo team withdrew from the French Grand Prix in July after Ascari crashed and died. In 1926, Maserati came out with the Tipo 26, its first highly competitive race car that led to Maserati winning the Constructors' title and Ernesto Maserati taking the Italian driving championship in 1927. Despite Maserati's strong performances, Campari claimed victory for Alfa Romeo in the 1927 Coppa Acerbo. The 1928 season saw Giuseppe Campari win his second consecutive Coppa Acerbo and his first at the Mille Miglia. He earned a second-place finish in the Targa Florio, a race he entered several times and although he frequently finished near the top, he never managed a win. The following year he repeated as champion at the Mille Miglia and along with top drivers such as Malcolm Campbell and Rudolf Caracciola, he traveled to Ireland to compete in the inaugural Irish International Grand Prix at Phoenix Park in Dublin. Run in front of more than 100,000 spectators, Campari was hit in the eye by a flying small rock but was successfully treated in hospital and the race was won by the Russian émigré, Boris Ivanowski. Campari also raced in the Tourist Trophy Races at the Ards course in Belfast where he finished second to Caracciola's Mercedes. In 1930, Tazio Nuvolari joined Campari on the Alfa Romeo team. After a sensational debut season, Nuvolari and Campari combined to win their first Italian Grand Prix, a victory that made them national heroes for taking the championship from the French who had won it for the past three years. That same year, Campari won his third Coppa Acerbo but for 1933 he became part of the Maserati team with Baconin Borzacchini and Luigi Fagioli. Campari won his second French Grand Prix driving for Maserati, but at age 41 was ready to retire at the end of the season. The Italian Grand Prix on September 10, 1933 at the Autodromo Nazionale Monza in Monza, Italy was to be his last race. After 20 years without any major accidents, disaster stuck in one of the blackest days in Grand Prix racing history. While leading the race, Campari was instantly killed when his car crashed after skidding in a sharp turn on a patch of leaked engine oil. Immediately behind him in second place, team-mate Baconin Borzacchini tried unsuccessfully to avoid Campari's wrecked vehicle and was killed when his car veered off the track. Later on, when the race was restarted, the vehicle of Polish driver, Count Stanislas Czaykowski, crashed and caught on fire, burning him to death. Personal life In addition to his love of automobile racing, Giuseppe Campari had two other passions: food, in great quantities that he liked to prepare himself, and the opera. Blessed with a great baritone voice from the depths of an expansive paunch, he took singing lessons and while still racing began to sing professionally. Major victories · Circuit of Mugello 1920, 1921 · Coppa Acerbo 1927, 1928, 1931 · French Grand Prix 1924, 1933 · Italian Grand Prix 1931 · Mille Miglia 1928, 1929 |

|

|

|

|