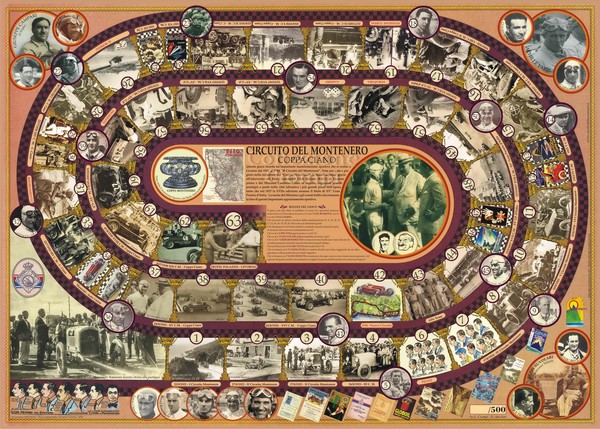

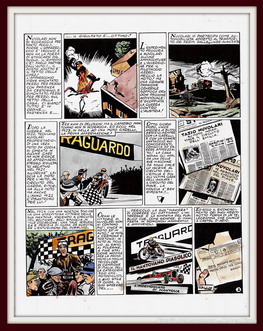

XI° CIRCUITO DEL MONTENERO

COPPA CIANO

|

||

| Istituto luce |

|

XI° CIRCUITO DEL MONTENERO

|

|

||

| Istituto luce |

| Introduzione | Articoli | Foto | Classifica e piloti |

Percorso | Pubblicità Pubblicazioni |

Coppa del Mare | Montenero Home |

|

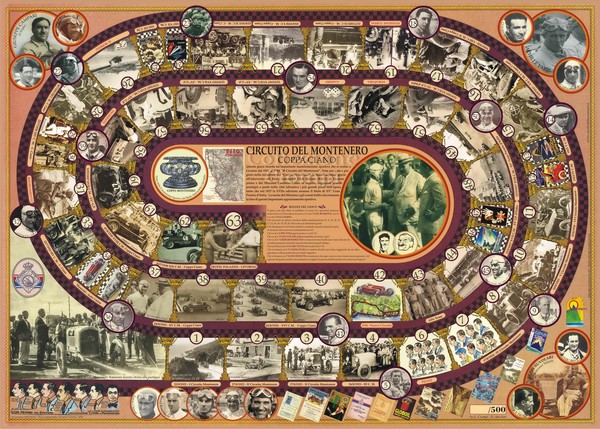

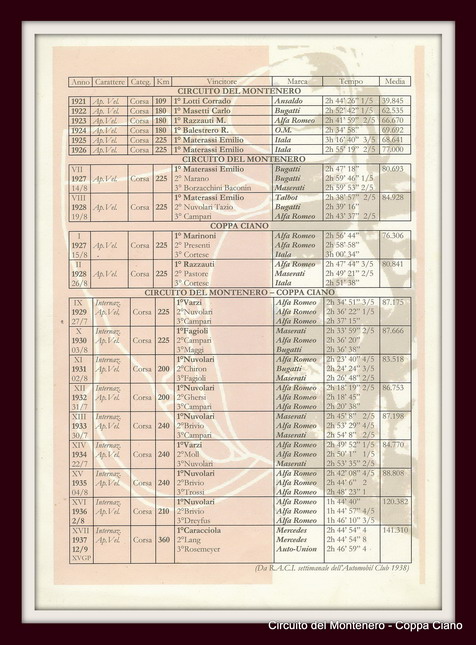

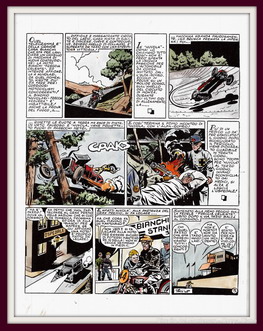

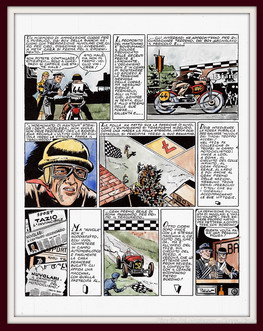

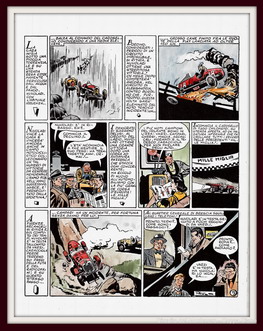

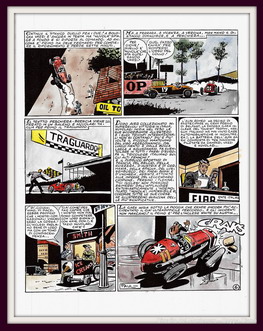

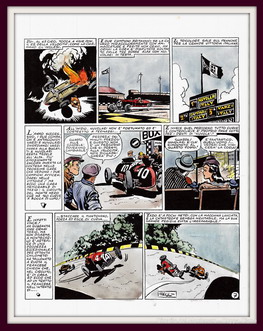

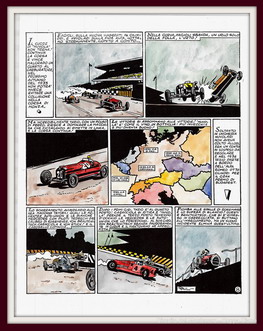

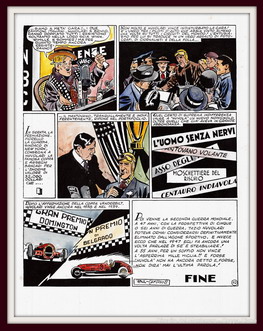

1931 - 2 agosto Percorso: Ardenza Mare (Rotonda), Ardenza Terra, Montenero, Savolano, Castellaccio, Romito, Calafuria, Antignano, Ardenza Mare (lunghezza 20 km) “XI Circuito del Montenero - Coppa Ciano” Formula Libera oltre 1100 cmc (10 giri - 200 km) 1) NUVOLARI Tazio, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.23’.40”.4/5 (media 83,518 km/h); 2) CHIRON Louis, su Bugatti, in 2h.24’.24”.3/5; 3) FAGIOLI Luigi, su Macerati, in 2h.26’.48”.2/5; 4) CAMPARI Giuseppe, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.27’.27”.2/5; 5) VARZI Achille, su Bugatti, in 2h.28’.56”; 6) CORTESE Franco, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.33’.32”; 7) D’IPPOLITO Guido, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.38’.39”; 8) TARUFFI Piero, su Itala, in 2h.39’.29”.2/5; 9) CASTELBARCO Luigi, su Bugatti, in 2h.39’.26”.2/5; 10) CARRAROLI Guglielmo, su Alfa Romeo, in 2h.42’.02”.2/5; Giro più veloce di Varzi Achille in 14’.00”.3/5 a 85,653 km/h. Vetturette 1100 cmc (8 giri- 160 km) 1) PREMOLI Luigi, su Salmson, in 2h.14’.03”.2/5 (media 71,611 km/h); 2) FERRARI Girolamo, su Talbot, in 2h.14’05”; 3) MATRULLO Francesco, su Salmson, 2h.16’39”; 4) PRATESI Albino, su Salmson, in 2h.16’.55”; 5) CIONI Giuseppe, su Fiat, in 2h.27’.51” Giro più veloce Premoli Luigi 16’.14” a 73,922 km/h. (Da: Maurizio Mazzoni: “Lampi sul Tirreno”, Firenze 2006) CIRCUITO MONTENERO 1931 (V COPPA CIANO) Montenero - Livorno (Italy), 2 August 1931. Over 1100cc: 10 laps x 20.0 km (12.4 mi) = 200.0 km (124.3 mi) Below 1100cc: 8 laps x 20.0 km (12.4 mi) = 160.0 km (99.4 mi) Drivers Class up to 1100cc 2 Alfredo Casali, Fiat 509 -1000cc; 4 Giorgio Lorenzini, Fiat 509 -1000cc; 6 Camillo Savelli, Fiat 509 -1000cc; 8 Umberto Capello, X -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 10 Luigi del Re, Fiat-Lombard AL3 -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 12 Macario Basagni, Fiat -1000cc (DNA - did not appear); 14 Giuseppe Cioni, Fiat 509 -1000cc; 16 Aldo Terigi, Salmson -1100cc; 18 Raffaele Luchini, X -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 20 Luigi Platé, Lombard AL3 -1100cc; 22 Eugenio Palumbo, Amilcar -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 24 Antonio Ferrando, Salmson -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 26 Albino Pratesi, Salmson -1100cc; 28 Catullo Lami, X 1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 30 Domingo Giorgi, Lombard AL3 -1100cc; 32 Gerolamo Ferrari, Talbot-Special 700 -1100cc; 34 Guglielmo Peri, X (DNA - did not appear); 36 Luigi Premoli, Salmson -1100cc; 38 Constanzo Arzilla, Amilcar -1100cc; 40 Leonardo Jeroniti, Salmson G.P. -1100cc; 42 Oddone Segrazzini, Maserati -1100cc (DNA - did not appear); 44 Francesco Matrullo, Salmson -1100cc; 46 Giuseppe Rossi, Fiat 509 -1000cc; Class over 1100cc 50 Clemente Biondetti, Maserati 26R -1700cc; 52 Pietro Ghersi, Bugatti T35B -2300cc; 54 Baconin Borzacchini, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc; 56 Giuseppe Campari, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc; 58 Achille Varzi, Bugatti T51 -2300cc; 60 Luigi Fagioli, Maserati 8C-2800 -2800cc; 62 Domenico Cerami, Maserati 26B MM -2000cc; 64 Louis Chiron, Bugatti T51 -2300cc; 66 Giovanni “Nini” Jonoch, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -2000cc; 68 Tazio Nuvolari, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc; 70 Amedeo Ruggeri, Talbot 700 -1500cc; 72 Francesco Severi, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc; 74 Raffaello Bartolucci, O.M. 665 -2200cc; 76 Renato Balestrero Bugatti T35 C -2000cc (DNS - reserve driver for #78); 78 Eugenio Fontana, Bugatti T35C -2000cc; 80 Carlo Gazzabini,Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 S -2300cc; 82 Guglielmo Carraroli, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc; 84 Franco Cortese, Alfa Romeo -1800cc; 86 Gaspare Bona, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc; 88 Umberto Klinger, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc; 90 Luigi Castelbarco, Bugatti T39A -1500cc; 92 Piero Taruffi, Itala 75 -2000cc; 94 Raffaello Fortuna, Bugatti (DNA - did not appear); 96 Carlo Di Vecchio, Talbot 700 -1500cc; 98 Amerigo Calzolari, O.M. 665 SSMM -2200cc; 100 Guido d'Ippolito, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc; 102 Domenico Cerami, Maserati (DNA - did not appear); 104 Giovanni Minozzi, Bugatti T35C- 2000cc; 106 Stefano Gyulai, Alfa Romeo 6C-1500 SS -1500cc; 108 Emilio Romano, Bugatti; 110 Renato Danese, Bugatti T35C- 2000cc (DNA - did not appear); 112 Apollonio Marini, O.M. (DNA - did not appear); 114 Georges d'Arnoux, Bugatti (DNA - did not appear); 116 X X , Bugatti (DNA - did not appear); 118 Romani, X (DNA - did not appear); 120 Bettoia, Alfa Romeo (DNA - did not appear); 122 Giovanni Serra, X (DNA - did not appear); 124 Secondo Corsi, Alfa Romeo (DNS did not start); 126 Giannini, X (DNA - did not appear); 128 Luigi Catalani, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc. Nuvolari wins the Coppa Ciano at Montenero in record time The international motor sport week at Livorno ended with the Coppa Ciano race, which proved to be another classic battle between Alfa Romeo, Bugatti and Maserati. Scuderia Ferrari represented Alfa Romeo with various 8C-2300 models driven by Campari, Nuvolari, Borzacchini and Cortese backed up by a variety of 6C-1750 types for Severi, Carraroli, Klinger and D'Ippolito. Maserati appeared with only one 2800 cc type 26M for Fagioli. Two potent Bugatti 2300 twin-cam models were privately entered by Chiron and Varzi but with factory backing. Besides these top drivers there were another 17 entries, all independents. At the start Varzi and Fagioli had the fastest cars but both soon ran into trouble. That made Nuvolari's life easier in his fight for the lead. Near the end Varzi (Bugatti) established the fastest lap while Chiron (Bugatti) almost caught up with the victorious Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) on the final lap. Fagioli (Maserati) finished in third place followed by Campari, Varzi, Cortese, D'Ippolito, Taruffi, Castelbarco and Carraroli. The small car class raced concurrently and was won by Premoli (Salmson) ahead of G. Ferrari (Talbot- Spcl.), Matrullo (Salmson), Pratesi (Salmson) and Cioni (Fiat). The races on the Montenero Circuit near Leghorn (Livorno) had been held since 1921. From 1922 onwards a 22.5 km circuit was used, which in 1931 was shortened to 20 km and routed from Ardenza Mare - Montenero - Savolano - Castellaccio - and back to Ardenza Mare. For 1931 the greater parts of the circuit was resurfaced, including the start and finish area after the tram tracks had been removed. The old row of 24 pits was replaced by a new 25-pits complex with a time keepers' stand and new timing display boards above the pits. The old grandstands made way for larger ones. The narrow road circuit still consisted of endless curves with steep up and down slopes. The 1931 event was the 11th time that the race was held on the Circuito del Montenero and the organizer named it misleadingly the 11th Coppa Ciano but in reality, 1931 was the 5th Coppa Ciano. The Coppa or trophy was donated by Italian Navy hero Costanzo Ciano for a 1927 Montenero sports car race, which was named after the trophy. The Coppa Ciano name was applied for the second time to the 1928 Montenero sports car race. As of 1929, when the sports car race was dropped from the program, the Coppa Ciano name was assigned to the racecar event for the first time. The races were held annually and 1931 was the fifth running of the Coppa Ciano and the eleventh race on the Montenero circuit. The RACI (Royal Automobile Club of Italy) and L'Automobile Club Livorno, staged a motorcycle race the week before the automobile race. The Coppa Ciano race results counted for the Italian Championship. The 20 km circuit had to be lapped ten times by the cars over 1100 cc but the smaller cars up to 1100 cc had to cover only eight laps or 160 km. A special prize was to be provided for the 1500 cc class for scoring in the Italian Championship. The total prize money was 215,000 lire of which 183,000 went to the large car class. 100,000 was to go to the victor plus the Ciano Cup, 40,000 lire to second place and the Mussolini Cup, 15,000 and the Livorno Cup to third, 10,000 to fourth, 7,000 to fifth, 5,000 to sixth, 4,000 to seventh and 2,000 to eighth. The first of the small car class received 5,000 lire and a gold medal, the second 3,000 and third 2,000 lire. There were additional prizes for the leader on each lap, totaling 22,000 lire. Entries Most of the renowned European race drivers were at the start for the Coppa Ciano except the Germans, who were busy at the Avusrennen. Ernesto Maserati and Tazio Nuvolari had entered for the German race but then withdrew to be present in Livorno. In the class over 1100 cc, 40 entries were assigned with race numbers. The Scuderia Ferrari entered a total of eight Alfa Romeos. Nuvolari had a 8C-2300 spider Zagato on loan from the factory with the slotted Monza cowl but lacking rear bodywork in Targa Florio configuration with spare wheel behind the barrel tank. Borzacchini had possibly a similar 8C-2300 and for local hero Franco Cortese from Livorno a 8C-2300, likely a Mille Miglia car. Campari had one of the double 6-cylinder 3500 cc type A monoposti on loan from the factory, which he drove only during early practice but then changed to a 8C-2300 borrowed from the factory. Severi, Carraroli, Klinger and D'Ippolito were driving several variations of the Scuderia's 6C-1750 Alfa Romeos. Gazzabini's Alfa was not supercharged; it was a 6C-1750 S which he co-owned with Paolo Cantono. The Bugattis of Chiron and Varzi were not official factory cars and were entered under the drivers' names. Nevertheless, it was an important race for Varzi in his red 2300 twin-cam Bugatti because the race was part of the Italian Automobile Championship. Chiron drove a similar car but painted blue. Fontana had a T35C Bugatti, probably ex-Balestrero who was present as his reserve driver. The Maserati factory only sent a single 2800 cc type 26M for Fagioli with a spare wheel on the right side. Taruffi drove an Itala 75, a supercharged 2-liter car which belonged to Lelio Pellegrini Quarantotti. Besides these drivers there were many additional entries, all independent, with no chance of winning the race. They are listed at the beginning of this report together with the 23 independent cycle car entries in the class up to 1100 cc. Alessandro Silva states that Gerolami Ferrari drove a Talbot Special which was a Bugatti chassis with a 1100cc engine made in Materassi's workshop from Talbot spares. Practice Wednesday was the first official practice from 12:30 to 14:30. The practice times of Corsi (Alfa) were 19m.26s and 18m.50s, Bertolucci (O.M.) 17m.21s and 17m.33s, Terigi (Salmson) 20m.51s, Ghersi with an Alfa 1750 in 16m.50s and Cerami (Maserati) 16m.25s. The popular Campari drove the 3.5-liter tipo A monoposto, which had been revised since Monza, and was timed at 15m.14s and later 14m.39s. The existing lap record, which stood at 14m.38.4s, had been established in 1930 by Nuvolari in an Alfa Romeo P2. On account of the shortening and improvements to the circuit better times could be expected. Thursday's practice again took place from 12:30 to 14:30 PM. Chiron, Varzi, Nuvolari, Campari and Prince Cerami circled around the track. Varzi was timed at 15m.03s, 14m.24s and 14m.19s. Chiron turned laps of 15m.35s and 15m.59s. It was the Frenchman's first time at the difficult Montenero circuit and it was obvious that he lacked knowledge about the multitude of twists and ups and downs. Ghersi changed cars, and now in a Bugatti, turned laps at 16m.55s and 15m.36s. Campari who continued to drive the tipo A monoposto, turned laps at 14m.58s, 14m.44s and 14m.26s. Prince Cerami was timed at 16m08s, 16m flat and 15m.52s. Nuvolari drove a 15m.26s lap, then followed with 14m.27s, 14m.13s and 14m.08s, beating the times established by Varzi, Campari and Borzacchini. Fortuna drove laps at 17m.43s and 17m.55s, while Corsi lapped at 18m.59s. Friday was the third and last day of practice. Many drivers were on the circuit and the following times were established. Nuvolari 14m.28s, Count Gyulai 16m.05s, Matrullo 17m.41s, Lami with the 1100 cc car 19m.04s, Chiron 14m.48s, Carraroli 16m.39s, Fagioli 14m.18s, Cortese 14m.42s and Severi 15m.39s. Varzi was registered three times with laps of 14m.13s, twice at 14m.02s and once even at 14 minutes flat. Campari turned a lap at 14m.37s with the 8C2300 Monza on loan from the factory. Corrado Filippini reported that Campari decided in the last moment not to race the tipo A monoposto during the race for unknown reasons. Race A crowd of over 100,000 witnessed the race, which was attended by the donor of the Cup, Minister of Communications Count Costanzo Ciano di Cortelazzo and Countess Carolina, the Countess Maria Ciano di Cortellazzo, Vincenzo Florio President of the RACI Sporting Commission, the Prince and Princess di Pimonte and other luminaries. From 63 entries some drivers did not appear or did not start. Consequently only 42 cars started, 14 in the class up to 1100 cc were present at the start area and behind them 28 large cars over 1100 cc. They were released in groups of three at an interval of one minute between each trio. This system was used as a safety precaution. Although the circuit had been shortened, resurfaced and corners rounded, it was still a very narrow road and difficult for drivers to pass each other. AUTOMOBIL-REVUE reported that the small cars up to 1100 cc started first and took off at 15:30. Grid (N°6) Savelli (Fiat) (N°4) Lorenzini (Fiat) (N°2) Casali (Fiat) (N°20) Platè (Lombard) (N°16) Terigi (Salmson) (N°14) Cioni (Fiat) (N°32) G. Ferrari (Talbot) (N°30) Giorgi (Lombard) (N°26) Pratesi (Salmson) (N°40) Jeroniti (Salmson) (N°38) Arzilla (Amilcar) (N°36) Premoli (Salmson) (N°46) Rossi (Fiat) (N°44) Matrullo (Salmson) At 15:34 when the last of the small cars had left the start area, the long anticipated big cars were to show their mettle. Grid (N°54) Borzacchini (Alfa) (N°52) Ghersi (Bugatti) (N°50) Biondetti (Macerati) (N°60) Fagioli (Alfa) (N°58) Varzi (Buratti) (N°56) Campari (Alfa) (N°66) Jonoch (Alfa) (N°64) Chiron (Bugatti) (N°62) Cerami (Maserati) (N°72) Severi (Alfa) (N°70) Ruggeri (Talbot) (N°68) Nuvolari (Alfa) (N°80) Gazzabini (Alfa) (N°78) Fontana (Bugatti) (N°74) Bartolucci (O.M.) (N°86) Bona (Alfa) (N°84) Cortese (Alfa) (N°82) Cararoli (Alfa) (N°92) Taruffi (Itala) (N°90) Castelbarco (Bugatti) (N°88) Klinger (Alfa) (N°100) D'Ippolito (Alfa) (N°98) Calzolari (O.M.) (N°96) Di Vecchio (Talbot) (N°108) Romano (Bugatti) (N°106) Gyulai (Alfa) (N°104) Minozzi (Bugatti) (N°128) Catalani (Alfa) The first row of Biondetti, Ghersi and Borzacchini was followed after one minute by Campari, Varzi and Fagioli. The third row consisted of Conte Cerami, Chiron and and Jonoch. Nuvolari started in the fourth row. When the cars returned from the first lap, Varzi and Fagioli were in the lead, next to each other both with the same time of 14m.32s. Chiron was doing remarkably well for someone who had never raced at Montenero before. Only 3 seconds slower than Varzi in a similar car and 8 seconds faster than Nuvolari, though the latter may have been held up by slower cars due to his fourth row start. During the lap Severi left the road. Klinger (Alfa Romeo) also retired after the first lap. The top drivers of the three makes had taken the front positions in the following order: 1. Varzi Bugatti 14m.32s 2. Fagioli (Maserati) 14m.32s 3. Chiron (Bugatti) 14m.35s 4. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 14m.43s 5. Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo) 14m.45s 6. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 15m.09s At the end of the second lap, Varzi still held the lead. Nuvolari had moved from fourth into second place, reducing his gap to the leader from 11 to just four seconds with a lap of 14m.21s. Chiron remained third and Fagioli fell back to fourth position, while Borzacchini retired with a clutch problem. Campari advanced to fifth, followed by Biondetti, Minozzi, Ghersi, Cortese and Castelbarco tenth. 1. Varzi (Bugatti) 2. Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 3. Chiron (Bugatti) 4. Fagioli (Maserati) 5. Campari (Alfa Romeo) 6. Biondetti (MB Speciale) 7. Minozzi (Bugatti) 8. Ghersi (Bugatti) 9. Cortese (Alfa Romeo) 10. Castelbarco (Bugatti) After the third lap Nuvolari was battling Varzi for the lead, instigating another battle of the leading Alfa and Bugatti drivers. They were clearly the fastest runners in the race. But a surprising incident brought an end to their fight, when Varzi slowed down and arrived with a flat tire at the pits. The fact that he was forced to drive slowly back to the pits plus the resultant tire change cost him over five minutes and robbed him of a possible victory. Varzi had fallen back to eighth position. Fagioli could not maintain Nuvolari's pace due to a slipping clutch, which made it impossible to keep going at his early pace. Chiron, although driving very well, was not going to endanger Nuvolari. He was just not fast enough similarly Campari, Ghersi, Biondetti and Cortese. On the third, fourth and fifth laps Nuvolari made very fast times of 14m.16s, 14m.15s and finally an amazing 14m.08s. So, after five laps Nuvolari was 1m.03s ahead of Chiron and about two minutes ahead of Fagioli in third place. After an even faster sixth lap in 14m.06s Nuvolari's advantage over Chiron increased to 1m.11s and on lap seven his lead had grown by another six seconds. Since he had started only one row behind Chiron, Nuvolari was now ahead of him on the road. The importance of this was that Chiron's pit could give their driver an up-to-date signal of Nuvolari's progress. After the eighth lap the Mantuan's advantage grew another four seconds, while Varzi gained fifth position. On the ninth lap, Nuvolari further increased his lead over Chiron while Varzi in fifth place established a new record lap of 14m.00.6s, compared with Nuvolari's best of 14m.06s. Fagioli held on to third place while Campari maintained fourth ahead of Varzi. During the tenth and last lap Chiron produced an absolutely excellent performance considering that he was new at this long twisting circuit. His fastest lap in 14m.08.6s helped him to reduce Nuvolari's advantage of 1m.31s to just 44 seconds. However, the main reason why Chiron came so close to Nuvolari was that the Mantuan had a small road accident on the tenth lap while coming down from the mountains. He lost valuable seconds as a result of damaging his car and having to slow his pace. The loudspeakers at the grandstand announced that Chiron had just passed Nuvolari coming down from the mountains. The enthusiasm of the Italian public rapidly dwindled away. Possibly the Italian's victory was now in question? But the first place for Nuvolari was not necessarily lost, since he had started one minute behind Chiron. When the Frenchman arrived and passed the finish line, great tension built up with the crowd in anticipation, concerned that Nuvolari would not reach the finish within the one minute. But then, 16 seconds later, there was great jubilation as Nuvolari reached the line as victor still 44 seconds ahead of Chiron, who was an honorable second. Fagioli, who maintained his third position, had to deal with a slipping clutch, but had no problem staying ahead of Campari and Varzi. Biondetti and Ghersi in seventh and eighth position retired as a result of accidents. Cortese held sixth position, while in seventh place was the skillful' D'Ippolito in the first of the 1750 Alfas. Notable were also Fontana, Taruffi, Castelbarco and Carraroli in the next places. However, Fontana was disqualified for being relieved by Balestrero away from the pits, which was a rule violation. 1100cc class The 1100 cc small car class, as anticipated, was won by Premoli in the Salmson monoposto. Premoli prevailed despite a rather chaotic race with stops at the pits to change plugs. On the last lap barely half a kilometer from the finish a crash between Premoli and Ferrari during their neck and neck race for first position brought both to a stop. Premoli recovered and finished two seconds ahead of Ferrari in his so-called Talbot 1100, which used a modified 1500 Talbot engine in a 1500 Bugatti chassis. The Roman Matrullo ended up third in a rather old Salmson amongst his opponents with the latest supercharged cars. Pratesi and Cioni were the last finishers in this class. Results, class over 1100 cc: 1°(N°68) Tazio Nuvolari, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc (10 Laps); 2h.23m.40.8s; 2°(N°64) Louis Chiron, Bugatti T51 -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.24m.24.6s + 43.8s; 3°(N°60) Luigi Fagioli, Maserati 8C-2800 -2800cc (10 Laps) 2h.26m.48.4s + 3m.07.6s; 4°(N°56) Giuseppe Campari, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.27m.27.4s + 3m.46.6s; 5°(N°58) Achille Varzi, Bugatti T51 -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.28m.56.4s + 5m.15.6s; 6°(N°84) Franco Cortese, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc (10 Laps) 2h.33m.32.0s + 9m.51.2s; 7°(N°100) Guido D'Ippolito, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (10 Laps) 2h.38m.39.0s +14m.58.2s; DSQ(N°78) Eugenio Fontana, Bugatti T35C -2000cc (10 Laps) (2h.39m.10s) disqualified; 8°(N°92) Piero Taruffi, Itala 75 -2000cc (10 Laps) 2h.39m.19.4s + 15m.38.6s; 9°(N°90) Luigi Castelbarco, Bugatti T39A -1500cc (10 Laps) 2h.39m.36.4s + 15m.55.6s; 10°(N°82) Guglielmo Carraroli, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (10 Laps) 2h.42m.02.4s + 18m.21.6s. DNF(N°52) Pietro Ghersi, Bugatti T35B -2300cc (9 Laps) crash; DNF(N°50) Clemente Biondetti, Maserati 26R -1700cc (9 Laps) (crash); DNF(N°66) Giovanni “Nini” Jonoch, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (9 Laps); DNF(N°70) Amedei Ruggeri, Talbot 700 -1500cc (9 Laps) (mechanical); DNF(N°86) Gaspare Bona, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (9 Laps); DNF(N°74) Raffaello Bartolucci, O.M. 665 -2200cc (6 Laps); DNF(N°80) Carlo Gazzabini, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 S -1800cc (5 Laps) (mechanical); DNF(N°108) Emilio Romano, Bugatti (5 Laps); DNF(N°128) Luigi Catalani, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (5 Laps); DNF(N°98) Amerigo Calzolari, O.M. 665 SSMM -2200cc (4 Laps); DNF(N°104) Giovanni Minozzi Bugatti T35C -2000cc (3 Laps); DNF(N°54) Baconin Borzacchini, Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 -2300cc (1 Lap) (clutch); DNF(N°62) Domenico Cerami, Maserati 26B MM -2000cc (1 Lap); DNF(N°88) Umberto Klinger, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1800cc (1 lap) (mechanical); DNF(N°72) Francesco Severi, Alfa Romeo 6C-1750 GS -1500cc (0 Laps) (left the road); DNF(N°96) Carlo di Vecchio, Talbot 700 -1500cc (0 Laps); DNF(N°106) Stefano Gyulai, Alfa Romeo 6C-1500 SS -1500cc (0 Laps); Fastest lap: Achille Varzi, (Bugatti) on lap 9 in 14m.00.6s = 85.7 km/h (53.2 mph) Winner's medium speed : 83.5 km/h (51.9 mph) Weather: sunny and hot. Results, class up to 1100 cc 1°(N°36) Luigi Premoli, Salmson -1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.14m.03.4s; 2°(N°32) Gerolamo Ferrari, Talbot Special 700 -1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.14m.05.6s (+ 2.6s); 3°(N°44) Francesco Matrullo, Salmson -1100cc(8 Laps) 2h.16m.39.8s (+2m.36.4s); 4°(N°26) Albino Pratesi, Salmson -1100cc (8 Laps) 2h.16m.55.0s (+2m.51.6s); 5°(N°14) Giuseppe Cioni, Fiat 509 -1000cc (8 Laps) 2h.27m.51.0s (+13m.47.6s); DNF(N°2) Alfredo Casali, Fiat 509 -1000cc (5 Laps); DNF(N°16) Aldo Terigi, Salmson -1100cc (5 Laps); DNF(N°46) Giuseppe Rossi, Fiat 509 -1000cc (4 Laps); DNF(N°6) Camillo Savelli, Fiat 509 -1000cc (3 Laps); DNF(N°20) Luigi Platé, Fiat-Lombard AL3 -1100 (2 Laps); DNF(N°40) Leonardo Jeroniti, Salmson G.P. -1100cc (2 Laps); DNF(N°30) Domingo Giorgi, Lombard AL3 -1100cc (1 Lap); DNF(N°38) Constanzo Arzilla, Amilcar -1100(0 Laps); DNF(N°4) Giorgio Lorenzini, Fiat 509 -1000cc (0 Laps); Fastest lap: Premoli (Salmson) on lap 7 in 16m.14.0s = 73.9 km/h (45.9 mph) Winner's medium speed: 71.6 km/h (44.5 mph) Weather: sunny and hot. In retrospect The starting grids, arranged in numerical order, were initially incomplete because race numbers for five late entry drivers could not be verified. With a June 2013 update all race numbers could be confirmed thanks to Alessandro Silva with information primarily from Gazzetta dello Sport. Thereafter we completed the starting grids, adding seven small cars and 11 large ones. Primary sources researched for this article: - Autocar, London; - AUTOMOBIL-REVUE, Bern; - Automobile Club Livorno manifestazioni; - AZ - Motorwelt, Brno; - IL LITTORIALE, Roma; - IL TELEGRAFO, Livorno; - L'Auto Italiana, Milano; - La Domenica Sportiva, Milano; - LA STAMPA, Torino; - Manifesto by RACI & Moto Club Livorno; - Motor Sport, London; - MOTOR und SPORT, Pössneck; - RACI settimanale, Roma: - Tutti Gli Sports, Napoli; (by Hans Etzrodt in: The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing) |

|

|

|

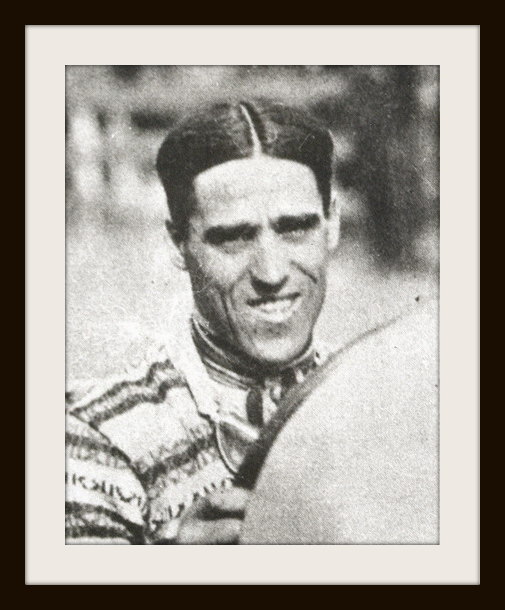

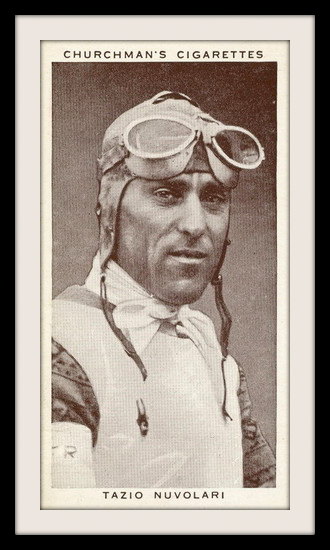

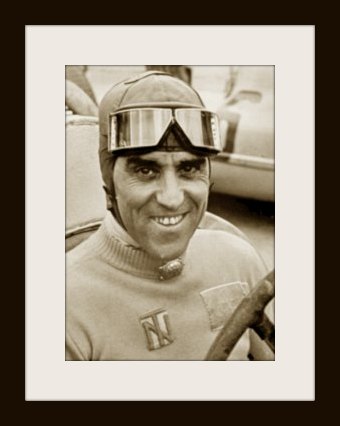

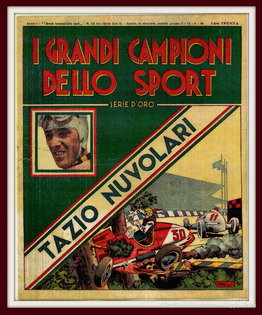

TAZIO NUVOLARI “Nuvolari – El Conductor de la emocion” Non è esistito nessuno come lui. Non ne esisterà mai nessuno. E quasi quasi verrebbe voglia di chiudere così quest’articolo, perché cos’altro si può dire ancora di Nuvolari, che non sia già stato detto, scritto, proclamato? Rimane una domanda, però: perché. Perché Nuvolari è stato così amato, fin dal primo istante in cui si presentò davanti ad un pubblico, un ometto con due baffetti alla Charlot, taciturno e concentrato, mingherlino e privo del “physique du role”, alla Campari o alla Amedeo Nazzari per intenderci. Perché soltanto a lui sono stati dedicati fiumi d’inchiostro, canzoni, tavole rotonde, francobolli, orologi, comitati, libri, trasmissioni televisive, automobili, musei, gran premi, rievocazioni, perché il suo nome, e soltanto il suo, è passato per antonomasia ad indicare la velocità, l’ardimento, l’irruenza? Cos’aveva di più di tutti gli altri, da farsi amare anche quando non vinceva, da farsi osannare sempre, dalla prima all’ultima gara della sua lunghissima carriera sportiva? Prendiamo una delle sue tante vittorie automobilistiche, quella conseguita al II Circuito di Biella del 1935, una affermazione importante ma inferiore a molte altre. Ecco come ne parlano i giornali, TUTTI i giornali, non solo quelli sportivi. “Il Littoriale” la definisce “una vittoria conquistata di forza”, e prosegue affermando che “la vittoria più che uno sprone alla lotta è un suo irresistibile credo” (splendida sintesi dello spirito nuvolariano). Le parole usate dal redattore sono quelle che saranno usate centinaia, migliaia di volte da altri giornalisti ed appassionati: “inizio travolgente”, “serrato duello”, “trionfatore acclamato”, “generosità di lottatore”. Il compassato “Corriere della Sera” parla di Nuvolari come di un “dominatore incontrastato”, di un “trionfatore che conferma le sue doti di stile e di ardire”, e della gara come “superba”. E la “Gazzetta del Popolo”? “Ha vinto trionfalmente facendo sfoggio di brio e di audacia, e riconfermandosi asso di grande classe”, “tagliando di prepotenza la curva, a denti digrignanti, tanto era lo sforzo che si imponeva” e concludeva descrivendo la folla che “aveva rotto ogni argine, tributandogli una di quelle entusiastiche dimostrazioni che costituiscono il premio più bello ed ambito per un atleta che abbia prodigato tutto se stesso nella contesa”. Naturale che la “Gazzetta dello Sport” definisse la gara di Nuvolari “una gara alla bersagliera”, e lo descrivesse “lanciato in uno dei suoi spettacolosi e fulminanti inseguimenti che entusiasmano le folle… ardente, combattivo e volitivo come sempre”. A un certo punto ai giornali mancarono gli aggettivi per descrivere le sue imprese. In occasione di una sua ennesima, bruciante vittoria, al Gran Premio di Francia del 1932, il “Guerin Sportivo” titolò: “Telegramma da Reims: niente di nuovo. 1° Nuvolari, su Alfa Romeo”. Fu il primo sportivo italiano a cui fu dedicato un libro: quello di Renato Tassinari (“Nuvolari. Ricordi di vita rapida”, Libreria Omenoni, Milano), uscito nel 1930, a soli due anni dalla sua prima importante affermazione automobilistica. Non era mai successo per nessun altro. Nel libro campeggia una foto che ritrae la Libreria Algani della Galleria Vittorio Emanuele di Milano: un grande cartello che sovrasta la porta d’entrata annuncia l’imminente uscita del libro. Com’era stato possibile il così rapido crearsi di un’epica, di una leggenda a tutt’oggi intramontata? Non era bello: un viso lungo e secco, cinquanta chili di ossa, come ci canta Dalla, una statura non elevata. Non era nemmeno giovane: inizia a correre in moto nel 1920, e di anni ne ha già ventotto (per inciso: è nato il 16 novembre 1892, lo stesso giorno e lo stesso mese della Scuderia Ferrari, trentasette anni più tardi). Quando Jano, direttore sportivo della Alfa Romeo, la mattina del 1° settembre 1925 lo vede gironzolare per l’Autodromo di Monza, e gli offre un giro di prova sulla P2, i meccanici hanno il loro da fare per sistemarlo, magro e segaligno com’era, sul seggiolino della vettura. Non é un esordio fulminante: tanto per cominciare, quella prova va a finire proprio male, con Nuvolari sbalzato fuori dalla vettura su un intrico di filo spinato che gli riduce a pezzi la schiena (e soprattutto il fondo della schiena). Non era neanche un “personaggio” che si prestasse facilmente ad interviste o ad incontri mondani: era poco loquace, e quando parlava sembrava scorticasse. Non si curava di andare troppo d’accordo, né con le case per cui correva, né con i piloti, avversari o compagni di squadra che fossero. Era rigoroso, certo del proprio valore, e non disposto a cedere di un millimetro, su nessuna questione. Per esempio alla Bianchi, nel 1928, quando ancora correva in moto, indirizzò una delle lettere di protesta più incredibili che mai un pilota sia stato costretto a scrivere alla “sua” casa. Era successo che la Bianchi, dopo una sua vittoria ottenuta battendo con una “350” anche moto di cilindrata superiore, aveva deciso di diminuirgli il premio con l’inaudita motivazione che era andato troppo piano. Nuvolari prese carta e penna, e non esitò a scrivere al Direttore Generale della Bianchi, commendator Gianfernando Tomaselli: “Formo la presente per informarla che in occasione di aver avvicinato la regolazione dei conti corse col sig. Zambrini dallo stesso venivo informato che Lei aveva disposto di trattenermi £ 2.000 sul Premio di Monza, e diminuendo la mia nota spese di £ 750 colla motivazione che sono andato adagio. – ma poteva essere rivolta a Nuvolari un’accusa così infamante? – “…se io non feci una corsa più veloce non è stata colpa mia ma bensì del sig. Zambrini che stanto al Bosk di rifornimento con segnali prima moderati e poi disperati erano sempre quelli che indicavano di rallentare. Io sul principio credevo nei segnali come discolpa da parte dei dirigenti la corsa dal Bosk in caso di eventuali guasti, mentre io ero troppo sicuro di come conducevo motore e macchina in quel momento, ma poi vista l’insistenza di rallentare ho dovuto con più dispiacere che dal piacere di aver vinto sopportare quella dolorosa decisione”. Conclude suggerendo di trattenere a Zambrini quello che si era ipotizzato di trattenere a lui. E dopo una lotta con la Bianchi che gli aveva fatto firmare un contratto in cui gli era vietata ogni corsa in automobile, decise di assaporare in pieno la libertà ritrovata, e di costituire egli stesso una sua scuderia (termine nuovo di zecca per gli sport del motore, appena coniato dal pilota Materassi che aveva costituito prima ancora di Nuvolari una squadra indipendente con quattro Talbot, così battezzata perché anche i piloti, come i fantini, guidavano dei cavalli). La scuderia di Nuvolari era costituita da quattro Bugatti, ed esordì al Gran Premio di Tripoli del 1928. Un’altra occasione in cui Nuvolari dimostrò tutta la sua irremovibile rocciosità. Il regolamento prevedeva che qualora a bordo non vi fosse il meccanico, fosse obbligatoria una zavorra di 70 kg. di sabbia. Materassi, che preferì non portarsi dietro il meccanico anche per non incorrere in eventuali beghe assicurative, trovò scomodissima nelle prove questa faccenda della zavorra: scivolava, non stava al suo posto, la sabbia si spargeva per l’abitacolo. Finì che chiese agli organizzatori di poter partire senza zavorra, e in questo modo si presentò alla linea di partenza. I commissari tergiversarono, discussero, cercarono una via d’uscita: e l’unica risultava ottenere il consenso di tutti gli altri piloti. Se fosse stato accordato, Materassi avrebbe potuto partire come voleva. Furono tutti d’accordo. Tranne uno. Nuvolari, ovviamente. Che non volle sentire ragioni: “Io porto il meccanico, lo porti anche lui, se non vuole la zavorra. Il regolamento da’ ragione a me”. Fine della faccenda. E Materassi non partì. Memorabile anche un’altra delle sue fulminanti repliche, stavolta alla Bugatti che sempre in quello stesso memorabile anno 1928 gli annunciò di averlo sostituito per la Targa Florio. Di risposta Nuvolari telegrafò a Bartolomeo Costantini, direttore sportivo della casa francese: “Lei ha solo cambiato corridore. Ma con questo non mi ha sostituito”. Non era un tipo facile, non c’era ragione perché dovesse esserlo. Nel 1932, all’Alfa Romeo gli avevano affiancato il tedesco Caracciola come compagno di squadra. E volevano anche farlo vincere, per motivi di immagine (dimostrare che era l’Alfa P3 ad essere imbattibile, non Nuvolari) e di opportunità commerciale (favorire le vendite in Francia e soprattutto in Germania). Al Gran Premio di Francia cercarono di convincere Nuvolari a dargli la precedenza, gli esposero persino la bandiera rossa, quella che significa “rallenta” o “dai strada”. Al traguardo, Nuvolari ebbe persino la faccia di stupirsi: “Bandiera rossa? Io l’avevo presa per verde, saranno stati gli occhiali verdi che indossavo! E comunque, poteva passarmi Caracciola, se era in grado…”. Al successivo Gran Premio di Germania far vincere Caracciola divenne una ragion di stato: era casa sua, un secondo posto sarebbe stato preso come un affronto! Si trovò una soluzione: far durare il rifornimento di Nuvolari di metà gara più del dovuto, in modo da ritardarlo. Funzionò, Nuvolari arrivò secondo. Ma non prima di aver lanciato maledizioni al cielo e manciate di candele ai meccanici neghittosi. E con Ferrari? Ciascuno dei due fu condizionato e legato alla vita dell’altro, in un’altalena di litigi e riappacificazioni, con il sottofondo di una grandissima stima e rispetto reciproci, se non una vera e propria amicizia. Lasciamo parlare direttamente Ferrari: “Nuvolari, a differenza di quasi tutti i piloti di ieri e di oggi, non ha mai sofferto per l’inferiorità del mezzo, non è mai partito battuto, ha sempre lottato leoninamente con qualsiasi tipo di vettura, anche per il settimo, il decimo posto in classifica. Certe sue vittorie, come quella al Gran Premio di Germania del 1935, sono rimaste imprese indimenticabili della storia automobilistica sportiva. Faceva notizia, faceva clamore anche quando non vinceva…Probabilmente nessuno accoppiava come lui una così elevata sensibilità della macchina a un coraggio quasi disumano…La sua tecnica rimase fino all’ultimo un prodigio dell’istinto ai limiti delle possibilità umane e delle leggi fisiche”. Forse comincia a delinearsi, il fascino di Nuvolari. E’ in quel suo essere tutto d’un pezzo. E’ in quel suo lottare sempre, per amore della lotta, in una nazione strenuamente competitiva come l’Italia che non si diverte se non può schierarsi, Varzi o Nuvolari, Binda o Guerra, Coppi o Bartali, tutti contro tutti. E’ in quel suo non avere altro motivo, altro motore, se non il pensiero di arrivare primo, fosse anche una corsa nei sacchi alla fiera del paese. Anche Ferrari si era chiesto “ma che cosa aveva di speciale lo stile di guida di Nuvolari, cos’aveva di diverso?” ed ecco la sua risposta. “Anch’io, dopo le prime gare combattute con lui, cominciai a domandarmi cosa avesse di speciale lo stile di quell’ometto smilzo e serio, il cui valore si rivelava di regola tanto più alto quanto maggiore era il numero delle curve…Così un giorno, alle prove del Circuito delle Tre Provincie nel 1931 gli chiesi di portarmi per un tratto sull’Alfa 1750 che la mia scuderia gli aveva dato…Alla prima curva ebbi la sensazione precisa che Tazio l’avesse presa sbagliata e che saremmo finiti nel fosso. Mi irrigidii in attesa dell’urto. Invece ci ritrovammo all’imbocco del rettilineo successivo con la macchina in linea. Lo guardai: il suo volto scabro era sereno, normale, non di chi è fortunosamente scampato ad un testacoda. Alla seconda e alla terza curva l’impressione si ripeté. Alla quarta o alla quinta cominciai a capire: intanto, con l’occhio di traverso, avevo notato che Tazio per tutta la parabola non sollevava il piede dall’acceleratore, e che anzi lo teneva a tavoletta. E di curva in curva scoprii il suo segreto. Nuvolari abbordava la curva alquanto prima di quello che l’istinto di pilota avrebbe dettato a me. Ma l’abbordava in un modo inconsueto, puntando cioè, d’un colpo, il muso della macchina contro il margine interno, proprio nel punto dove la curva aveva inizio. A piede schiacciato – naturalmente con la giusta marcia ingranata prima di quella sua spaventevole “puntata” – faceva così partire la macchina in dérapage sulle quattro ruote, sfruttando la spinta della forza centrifuga, tenendola con la forza traente delle ruote motrici. Per l’intero arco, il muso della macchina sbarbava la cordonatura interna, e quando la curva terminava e si apriva il rettifilo, la macchina si trovava già in posizione normale per proseguire diritta la corsa, senza necessità di correzioni”. A questo coro di voci, che dal passato riemergono per farci correre almeno una volta accanto a Nuvolari, aggiungiamo quella del grande giornalista Canestrini, anch’egli una volta costretto a fare un giro con lui. “Superammo i tornanti sopra Trafoi regolarmente, ma appena entrati nel tratto veloce, cominciai a pensare che Tazio prendeva troppa confidenza con il muretto di protezione che divide la strada dal precipizio, e che io vedevo sfiorare a pochi centimetri. Per farmi coraggio pensavo che, alla fine, una morte a fianco di un così grande campione, sarebbe stata ad ogni modo una bella morte. Puntato con le mani contro il bordo della carrozzeria, per non essere sbalzato fuori dalla macchina, superata la seconda serie di tornanti, mi accorsi che all’imbocco dell’undicesimo Nuvolari non accennava a frenare. Ebbi appena il tempo di pensare “ma che diavolo fa?” che Tazio dette un energico colpo di freno, cacciò dentro la seconda e poi prima ancora di completare la curva voltandosi verso di me gridò: “Accidenti, questa non me la ricordavo!” “Ce ne sono ancora 34” gli urlai all’orecchio”. E’ in questo “coraggio disumano”, come lo definì Ferrari, che sta racchiuso il segreto della sua immensa popolarità? Innumerevoli gli aneddoti sorti intorno alla sua guida. Si racconta che in un punto della discesa tra Montenero e Livorno, vi era una curva con un piccolo distributore, collocato appena al di la’ della carreggiata. Nuvolari, per guadagnare qualche centimetro e perciò qualche decimo di secondo, non esitava ad infilare la curva passando all’interno del ridottissimo spazio tra la pompa di benzina e la casa retrostante, un passaggio che dei meccanici di Ferrari, increduli, vollero misurare. Era di qualche centimetro più ampio della larghezza della macchina di Tazio: una cosa da brivido. Aveva una abilità sovrumana nello sfiorare ogni volta il limite, ma non in senso figurato: per guadagnare un metro sugli avversari, riteneva che il sistema più semplice fosse sfiorare il più possibile, a rischio di urtare, il marciapiede, le balle di sabbia, la cordonatura, pennellando la curva, e abbreviando ogni volta il tracciato. Ci voleva però non soltanto coraggio: bensì anche una magistrale capacità di calcolo e di padronanza della vettura. Ciò sfata una delle leggende, una delle tante, su Nuvolari: che il suo fosse un modo di guidare alla scavezzacollo, istintivo, improvvisato, tutto cuore e niente ragionamento, in piena contrapposizione con lo stile di Varzi, tutto calcolo e fredda passione. E’ una leggenda che fa torto ad entrambi: perché Varzi fu in realtà uomo di passione e passioni devastanti, tanto da distruggersi per una donna come uno degli eroi più romantici e tenebrosi del suo tempo; e Nuvolari fu un attento e sicuro gestore di se stesso e del suo immenso talento. Cambiò ripetutamente colori, e un paio di volte in modo clamoroso: nel 1933, quando ritenne di poter guadagnare molto di più mettendosi in proprio e lasciò la Scuderia Ferrari, e nel 1938, quando a 46 anni iniziò una seconda carriera passando alla Auto-Union. La vicenda del “divorzio” da Enzo Ferrari sfiorò le soglie dei tribunali: pare che il pilota avesse addirittura chiesto di cambiare il nome della Scuderia Ferrari in Scuderia Ferrari-Nuvolari. Per Ferrari una richiesta inconcepibile, ed inaccettabile; per Nuvolari, nient’altro che il riconoscimento del suo ruolo all’interno della squadra. Egli non si sentiva soltanto pilota ma, come già nel 1928 quando aveva creato la propria personale scuderia (e ancora tutti si ricordavano i camion con il suo nome scritto a caratteri cubitali sulle fiancate) un protagonista a tutto tondo. Un attento manager di se stesso, un’innata capacità di darsi alla folla e incatenarla allo spettacolo della sua guida: due doti che è raro trovare appaiate. Quando il suo rapporto con Ferrari si interruppe per la prima volta, nel 1933, si disse che erano stati gli esigui guadagni a spingerlo a correre per conto suo. Ferrari non replicò subito ma l’anno seguente fece un po’ i conti in tasca a Nuvolari, a Varzi e ad altri sulle pagine della rivista che la sua scuderia faceva uscire periodicamente. “In cinque anni – scrisse - la Scuderia ha erogato a piloti italiani oltre 2.300.000 per il reparto auto e quasi £ 50.000 in due anni per il reparto moto… Un corridore italiano che fece parte della nostra organizzazione ha guadagnato in una stagione sportiva di sette mesi £. 600.000; i guadagni degli altri piloti furono individualmente e annualmente inferiori, ma sempre hanno costituito un massimo rispetto a quanto essi avrebbero potuto guadagnare correndo isolatamente o alle dipendenze di una casa costruttrice…Se questo corridore ci ha abbandonato gli è che iperboliche debbono essere state le offerte ricevute. Aggiungiamo che un altro, il quale abbandonò pure la nostra organizzazione per andare all’estero, aveva guadagnato £ 140.000 in meno di tre mesi di attività e ci lasciò unicamente perché di solo stipendio ottenne £ 500.000, cifra di cui non potevamo logicamente disporre; e che un altro ancora in soli quattro mesi percepì £ 300.000”. Quelle seicentomila lire del 1934 corrispondono oggi a circa 500.000 euro: non male. Nella seconda metà del 1933 e nel 1934 Nuvolari è quindi un pilota indipendente: corre su vetture Maserati, battendo in più occasioni le Alfa Romeo della Scuderia Ferrari. Fu contattato dalla Auto-Union che gli fece guidare un paio di volte in prova una delle sue monoposto ma non si arrivò all’ingaggio, a causa di una fiera opposizione all’interno della stessa squadra Auto- Union, e segnatamente, pare, da parte di Hans Stuck: troppo scomodo un “collega” come Tazio, troppo grande il rischio di venirne completamente oscurati. Si arrivò dunque, a fine 1934, alla “pace” con Enzo Ferrari. Nuvolari tornò a correre con le Alfa Romeo della scuderia modenese e nel biennio 1935-1936 conquistò alcuni dei suoi più sensazionali successi. Ma dopo l’annata del 1937, in cui le Mercedes conquistano sette gare su tredici, cinque vengono vinte dalla Auto-Union e una soltanto dall’Alfa Romeo, la situazione ridiventa molto difficile. Nuvolari non può continuare a correre su vetture così inferiori alla concorrenza. “La trovata di Tazio Nuvolari”, commenta Auto Italiana del 30 agosto 1937, all’indomani del rinnovato contatto tra il pilota italiano e la casa tedesca, sfociato nella partecipazione al Gran Premio di Berna al volante di una Auto-Union. “Il G.P. di Berna non offrirebbe altra materia di commento se non fosse per il caso Nuvolari, che ha un po’ commosso l’opinione pubblica italiana…La faccenda ha destato parecchio rumore, tanto che non sono mancate le voci secondo le quali l’asso mantovano avrebbe abbandonato l’Alfa Romeo per passare sotto i colori della marca germanica…Il gesto si è prestato a discussioni, e se può essere compreso da quanti conoscono bene l’irrequieto mantovano, da’ modo tuttavia a molti di pensare che dopo tutto poteva anche essere risparmiato”. Insomma, è opinione della rivista, “un increscioso episodio nella sua luminosa carriera”. Per ora è soltanto un episodio. Ma nel 1938 l’ulteriore perdita di competitività delle Alfa Romeo peggiora la situazione. Nuvolari si ferisce in un incidente a Pau e annuncia addirittura di voler rinunciare alle corse. Poi si rimette, fa un viaggio ad Indianapolis, dove non trova una vettura passabile e quindi non gareggia. Infine torna e tratta con Auto-Union (in difficoltà perché deve sostituire Rosemeyer, uccisosi in gennaio in un tentativo di record). Il contratto non è firmato subito, perché Nuvolari deve attendere il nulla osta della FASI (Federazione Automobilistica Sportiva Italiana) per gareggiare con vetture di marca estera. Nulla osta che gli viene concesso il 15 luglio 1938: l’inizio di una nuova, ennesima, carriera, per un pilota che secondo la stampa, impietosa anche con gli idoli, “cominciava ad accusare il peso degli anni”. Se ne accorsero, gli altri piloti, di quanto Nuvolari accusasse il peso degli anni! La sua carriera non soltanto non era finita (lo attendevano i trionfi di Monza, Donington, Belgrado), ma sembrò non finire mai, neanche nel dopoguerra, quando ancora sbalordì con due straordinarie partecipazioni alle Mille Miglia del 1947 e 1948. Nuvolari smise di correre soltanto nel 1950, a cinquantotto anni: un altro record. Nessuno potrà mai spiegare completamente la malia di Nuvolari, che qualcosa di magico l’aveva fin nel nome, così perfetto per il pilota dell’inosabile. Uno degli episodi, tra leggenda e realtà, che meglio lo ritraggono, è quello che lo vede protagonista del Gran Premio di Sitges, il 28 ottobre 1923. La pista ha una strana forma a fagiolo, con due curve paurosamente sopraelevate, raccordate ai rettifili da tratti troppo brevi e dunque pericolosa. Anche ad anni di distanza di una sola cosa si ricordavano gli organizzatori: della sua prestazione su una Chiribiri. Era arrivato quinto, battendosi come un leone. Ma era un episodio avvenuto durante le prove ad essere entrato nella leggenda. Nuvolari aveva convinto a salire sulla sua macchina la figlia del proprietario dell’Albergo Miramar, dove era alloggiato, scommettendo con gli amici che al culmine di una delle curve l’avrebbe baciata. E così fece, quasi sospeso nel vuoto su quella parete verticale (la ragazza peraltro era talmente paralizzata dal terrore da non opporre certo resistenza). Ritornata al box, la giovane donna svenne, tra le grida di acclamazione del giovane temerario. Quello che le cronache non dicono, è che quando rinvenne, al conductor de la emociòn, come fu definito il giorno dopo dai quotidiani spagnoli, venne mollata una sonora sberla. RIEPILOGO RISULTATI CORSE IN MOTO 125 corse, 78 vittorie di cui 39 assolute, 39 di classe, 41 giri più veloci, 4 record di velocità, 2 volte Campione d’Italia. RIEPILOGO RISULTATI CORSE IN AUTO 229 corse, 104 vittorie di cui 66 assolute e 38 di classe, 59 giri più veloci, 71 ritiri. MARCHE MOTOCICLISTICHE CON CUI CORSE NUVOLARI Della Ferrera, Saroléa, Harley Davidson, Fongri, Norton, Garelli, Indian, BSA, Borgo, Bianchi. MARCHE AUTOMOBILISTICHE CON CUI CORSE NUVOLARI Scat*, Ansaldo, Chiribiri, Bianchi, Bugatti, Talbot, Alfa Romeo, MG, Maserati, Auto Union, Fiat, Cisitalia, Ferrari, Abarth. LA PRIMA GARA: al IV Circuito Internazionale di Cremona, il 20 giugno 1920, sulla moto Della Ferrera. L’ULTIMA GARA: alla X Salita al Monte Pellegrino, il 10 aprile 1950, sulla vettura Cisitalia Abarth. BIBLIOGRAFIA SU NUVOLARI -“Nuvolari. Ricordi di vita rapida”, di Renato Tassinari, Libreria Editrice degli Omenoni, Milano, 1930 -“Il romanzo di Nuvolari”, di Luigi Marinatto, Edisport, Milano, 1957 -“Nuvolari”, di Giovanni Lurani, Cassell & Co., London, 1959 -“Nuvolari”, di Sergio Busi, Cappelli Editore, Bologna, 1965 -“Nuvolari”, di Rico Steinemann, Moderne Verlag GmbH, Munchen, 1967 -“L’antileggenda di Nuvolari”, di Cesare De Agostini”, Sperling & Kupfer, Milano, 1972 -“Nuvolari. Il mantovano volante”, di Aldo Santini, Rizzoli Editore, Milano, 1983 -“Tazio vivo”, di Cesare De Agostini e Gianni Cancellieri, Conti Editore, San Lazzaro di Savena, 1987 -“Nuvolari”, di Filippo e Fabio Raffaelli, Alfredo Cazzola Editore, Bologna 1991 -“Tazio Nuvolari” di Franco Zagari, Automobilia, Milano, 1992 -“Quando corre Nuvolari”, di Valerio Moretti, Edizioni di Autocritica, Roma, 1992 -“Nivola vola”, di Pablo Echaurren, Maurizio Corraini Editore, Mantova, 1992 -“Tazio Nuvolari Antologia”, autori vari, Edizioni Legenda, Milano 2003 -“Nuvolari. La leggenda rivive”, di Cesare De Agostini, Giorgio Nada Editore, Vimodrone, 2003 (*)una foto del 1915 ritrae Nuvolari al volante di una vettura Scat con numero di gara, però non risulta che vi abbia mai corso L’autrice ringrazia Gianni Cancellieri per la preziosa consulenza. Donatella Biffignandi (per “Auto d’Epoca” di maggio 2003) TAZIO NUVOLARI Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari (November 16, 1892 – August 11, 1953) was an Italian motorcycle and racecar driver, known as “Il Mantovano Volante” (The Flying Mantuan) or “Nivola”. He was the 1932 European Champion in Grand Prix motor racing. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche called Nuvolari “The greatest driver of the past, the present, and the future”. Tazio Nuvolari started out in motorcycle racing in 1920 at the age of 27. In 1925 he captured the 350cc European Championship. From then until the end of 1930, he competed both in motorcycle racing and in automobile racing. For 1931, he decided to concentrate fully on racing cars and agreed to race for Alfa Romeo's factory team, Alfa Corse. In 1932 he took two wins and a second place in the three European Championship Grands Prix, winning him the title. He won four other Grands Prix including a second Targa Florio and the Monaco Grand Prix. After Alfa Romeo officially left Grand Prix racing, Nuvolari stayed on with Scuderia Ferrari who ran the Alfa Romeo cars on a semi-official basis. During 1933, Nuvolari left the team for Maserati after becoming frustrated with the Alfa Romeo's performance. At the end of 1934, Maserati pulled out of Grand Prix racing and Nuvolari returned to Ferrari, who were reluctant to take him back, but were persuaded by Mussolini, the Italian prime minister. The relationship with Ferrari turned sour during 1937, and Nuvolari raced an Auto Union as a one-off in the Swiss Grand Prix that year before agreeing to race for them for the 1938 season. Nuvolari remained at Auto Union until Grand Prix racing was put on hiatus by World War II. The only major European Grand Prix he never won was the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix. Upon his return to racing after the war, he was 54 and suffering from ill health. His final race, in 1950, saw him finish first in class and fifth overall. He died in 1953 from a stroke. Personal and early life Nuvolari was born in Castel d'Ario near Mantua on 16 November 1892 to Arturo Nuvolari and his wife Elisa Zorzi. The family were well acquainted with motor racing as Arturo and his brother Giuseppe were both bicycle racers - Giuseppe was a multiple winner of the Italian national championship and was particularly admired by a young Tazio. Nuvolari was married to Carolina Perina, and together they had two children: Giorgio (born 4 September 1918), who died in 1937 aged 19 from myocarditis, and Alberto, who died in 1946 aged 18 from nephritis. Career: Motorcycle racing Nuvolari gained his license for motorcycle racing in 1915 at the age of 23. His motorcycling career was postponed, however, by the outbreak of World War I and Nuvolari served as a driver in the Italian army. Once the war had ended, he resumed his sporting career and took part in his first race at the Circuito Internazionale Motoristico in Cremona in 1920. During this period, Nuvolari also dabbled in car racing, winning a reliability trial in 1921. In 1925, Nuvolari became the 350 cc European Motorcycling champion by winning the European Grand Prix. At the time, the European Grand Prix was considered the most important race of the motorcycling season and the winners in each category were designated European Champions. Nuvolari also won the Nations Grand Prix four times between 1925 and 1928 and the Lario Circuit race five times between 1925 and 1929, all in the 350 cc class and each time on a Bianchi motorcycle. It was also in 1925 that Nuvolari was asked by Alfa Romeo to have a trial in their Grand Prix car. The car's gearbox seized and Nuvolari crashed, severely lacerating his back. Despite his injuries, he competed in the Nations Grand Prix at Monza six days later, winning the race after he had persuaded staff at the hospital to bandage him in a manner such that he could sit on his motorcycle and receive a push start. A switch to four wheels 1931-1932: Alfa Corse Coppa Consuma 1930, Tazio Nuvolari driving Alfa Romeo 6C1750GS. In 1930, Nuvolari won his first RAC Tourist Trophy (he won one more time in 1933). According to a legend, when one of the drivers broke the window of a butchery, Nuvolari, when passing by it, drove on the pavement and tried to catch a ham. According to Sammy Davis who met him there, Nuvolari showed a great sense for dark humour and seemed to enjoy situations when everything went wrong. For example, he told Enzo Ferrari after he got a ticket for a journey home from the Sicilian Targa Florio "What a strange businessman you are. What if I am brought back in a coffin?" Nuvolari and his co-driver Battista Guidotti in Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 GS spider Zagato won the Mille Miglia, becoming the first to complete the race at an average speed of over 100 km/h (62 mph). Due to starting after his team-mate Achille Varzi, he was leading the race despite still being behind Varzi on the road. In the dark of night Nuvolari tailed Varzi for tens of kilometres, riding at speed of 150 km/h (93 mph) with his headlights off, thereby being invisible in Varzi's rear-view mirrors; he then switched on his headlights before overtaking "the shocked" Varzi near the finish at Brescia. 1931 Towards the end of 1930, Nuvolari made a decision to stop racing motorcycles and to concentrate fully on car racing during 1931. The new season saw a change in the regulations which meant that Grand Prix races had to be at least 10 hours in duration. After drawing ninth place on the grid at the Italian Grand Prix, Nuvolari started the race in an Alfa Romeo shared with Baconin Borzacchini. However, the car had to retire with mechanical problems after 33 laps. Nuvolari then teamed up with Giuseppe Campari and the pair took the race win, although Nuvolari could not receive the championship points from it. Apart from a second place at the Belgian Grand Prix, the only other European Championship race, the French Grand Prix, resulted in a disappointing 11th place finish. Aside from the main European Championship Grands Prix, Nuvolari took victories in the Targa Florio and the Coppa Ciano. 1932 1932 saw a revision of the previous year's regulation change, with the race duration being reduced to between five and ten hours. The season was the only one in which Nuvolari regularly had one of the fastest cars, the Alfa Romeo P3. A consequence was that in the three European Championship Grands Prix, he took two wins and a second place - winning the championship by four points from Borzacchini. He took four other wins during the season, including the prestigious Monaco Grand Prix and a second Targa Florio. His mechanic Mabelli said about this race: "Before the start, Nuvolari told me to go down on the floor of the car everytime he shouts, which was a signal that he went to a curve too fast and that we need to decrease the car´s center of mass. I spent the whole race on the floor. Nuvolari started to shout in the first curve and wouldn't stop until the last one." On 28 April that year he was given a golden turtle badge by the famous Italian writer Gabriele d'Annunzio which symbolised the opposite of his speed. He wore the turtle ever since and it became his talisman and also his symbol. 1933-1937: Scuderia Ferrari and Maserati "Tazio Nuvolari was not simply a racing driver. To Italy he became an idol, a demi-god, a legend, epitomising all that young Italy aspired to be; the man who 'did the impossible', not once but habitually, the David who slew the Goliaths in the great sport of motor racing. He was Il Maestro." 1933 The 1933 season was the first year of a two year hiatus for the European Championship, and saw Alfa Romeo stop their official involvement in Grand Prix racing. They did not disappear altogether as they were represented by Enzo Ferrari's privateer effort. For economic reasons, the P3 was not passed on to Ferrari and they were forced to use the Monza, the predecessor of the P3. Maserati were their main opposition with a highly improved car. Nuvolari is often reported as having been involved in a race-fixing scandal at the Tripoli Grand Prix. It is said he, along with Achille Varzi and Baconin Borzacchini, conspired to fix the race in order to profit from the Libyan state lottery. The lottery saw 30 tickets drawn before the race - one for each starter - and the holder of the ticket corresponding to the winning driver would win seven and a half million lire. However, this story is said by some to be a work of fiction by Alfred Neubauer, the team manager of Mercedes-Benz at the time and a well-known raconteur with a penchant for spicing up a story. Some of the facts in Neubauer's version do not hold true with documented records of events, which point to Nuvolari, Varzi and Borzacchini agreeing to pool the prize money should one of them win, as opposed to Neubauer's claims of race fixing. Alfa Romeo announced that for the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Nuvolari would be competing in a team with Raymond Sommer. Sommer argued that he would be drive the majority of the race as he was more familiar with the circuit and Nuvolari would likely break the car. Nuvolari countered that he was a leading Grand Prix driver and Le Mans was a simple layout that would not trouble him, to which Sommer backed down and they agreed to divide the driving equally. The race itself saw Sommer and Nuvolari take a two lap lead before their fuel tank developed a hole, which was plugged by chewing gum whilst in the pits. Several more pit stops were necessary as the makeshift repair came undone several times during the race. Nuvolari drove from then until the end of the race, breaking the lap record nine times and winning the race by approximately 400 yards (366 m). 1934 "Let any who say it was foolhardy at least be honest and admit it was one of the finest exhibitions of pluck and grit ever seen. By such men are victories won!" Earl Howe, on Nuvolari's drive in the 1934 AVUS-Rennen whilst having one leg in plaster At the start of 1934, Nuvolari entered the Monaco Grand Prix in a privately owned Bugatti. Having made it up to third place in the race, he suffered brake troubles and fell back to fifth at the finish, two laps behind the winner, Guy Moll. Whilst racing at Alessandria in the Circuito di Pietro Bordino race, Nuvolari crashed whilst avoiding Carlo Felice Trossi's stricken car. He broke a leg, but suffering from boredom in hospital, he decided to enter the AVUS-Rennen just over four weeks after his accident. His Maserati was specially modified so that he could use all three of its pedals with his left foot; his right was still in plaster. Troubled by cramp, Nuvolari finished fifth. By the time of the Penya Rhin Grand Prix in late June, Nuvolari's leg was finally out of plaster, but was still causing him troubles as he battled pain until he retired his Maserati with technical problems. In the Italian Grand Prix, Nuvolari debuted Maserati's new 6C-34 model. The car performed poorly and Nuvolari could only finish fifth, three laps behind the Mercedes-Benz of Rudolf Caracciola and Luigi Fagioli. 1935 For 1935, Nuvolari set his sights on a drive with the German Auto Union team. The team were lacking top-line drivers, but relented to pressure from Achille Varzi who did not want to be in the same teams as Nuvolari. Nuvolari then approached Enzo Ferrari, but was turned down as he had previously walked out on the team. However, Mussolini, the Italian prime minister, intervened and Ferrari backed down. In this year, Nuvolari scored his most impressive victory, thought by many to be the greatest victory in car racing of all times, when at the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, driving an old Alfa Romeo P3 (3167 cm³, compressor, 265HP) versus the dominant, all conquering home team's cars of five Mercedes Benz W25 (3990 cm³, 8C, compressor, 375 hp (280 kW), driven by Caracciola, Fagioli, Hermann Lang, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Geyer) and four Auto Union Tipo B (4950 cm³, 16C, compressor, 375 hp (280 kW), driven by Bernd Rosemeyer, Varzi, Hans Stuck and Paul Pietsch). This victory is known as "The Impossible Victory". The crowd of 300.000 applauded Nuvolari, but the representatives of the Third Reich were enraged. 1936 Nuvolari had a big accident in May during practice for the Tripoli Grand Prix and it is alleged that he broke some vertebrae. Despite a limp, he took part in the race the following day and finished eighth. 1937 At the beginning of 1937, Alfa Romeo took their works team back from Ferrari and entered it as part of the Alfa Corse team. Nuvolari stayed with Alfa Romeo despite becoming increasingly frustrated with the poor build quality of their racing cars. At the Coppa Acerbo, Alfa Romeo’s new 12C-37 car proved to be slow and unreliable. This frustrated Nuvolari, who handed his car over to Giuseppe Farina mid-race. Not wanting to leave Alfa Romeo, he drove an Auto Union in the Swiss Grand Prix as a one-off. After the Italian Grand Prix, Alfa Romeo withdrew from racing for the remainder of the season and dismissed Vittorio Jano, their chief designer. 1938 Although Nuvolari started 1938 as an Alfa Romeo driver, a split fuel tank in the first race of the season at Pau was enough for him to walk out on the team, critical of the poor workmanship that was exhibited. He announced his retirement from Grand Prix racing and took a holiday in America. At the same time, Auto Union were having to rely on inexperienced drivers. Following the Tripoli Grand Prix they contacted Nuvolari who, having been refreshed from his break, agreed to drive for them. Post-war racing In 1946, Nuvolari raced in the Milan Grand Prix using only one hand to steer; the other was holding a bloodstained handkerchief over his mouth. Nuvolari's last race was in 1950 at the Palermo-Monte-Pellegrino hillclimb, in which he came first in his class and fifth overall. Death and legacy Nuvolari never formally announced his retirement, but his health had deteriorated and he became increasingly solitary. In 1952 he suffered a stroke which left him partially paralysed, and he died in bed a year later from a second stroke. Almost the entire town of Mantua attended his funeral, which is said to have seen an attendance of between 25 and 55 thousand people. The funeral procession was a mile long, and Nuvolari’s coffin was placed on a car chassis which was pushed by Alberto Ascari, Luigi Villoresi and Juan Manuel Fangio. Nuvolari has had four cars named after him - the Cisitalia 202 spider "Nuvolari", the Alfa Romeo Nuvola, the EAM Nuvolari S1, and the Audi Nuvolari Quattro. Nuvolari was one of the early proponents (if not the inventor, according to Enzo Ferrari) of the four-wheel drift technique. The technique was later utilised by drivers such as Stirling Moss. In 1976, Italian singer-songwriter Lucio Dalla wrote the song Nuvolari celebrating his myth. The song is still very famous in Italy, and it's part of Dalla's album Automobili (Cars). An Italian pay-TV channel dedicated to motor sports is also named Nuvolari. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|